Veröffentlicht: 27. Oktober 2018 – Letzte Aktualisierung: 21. September 2022

[The English text begins after a short introduction in German]

Philip Boyes forscht an der University of Cambridge, wo er sich mit dem östlichen Mittelmeerraum und besonders der Levante in der späten Bronze- und der frühen Eisenzeit, Handel und kulturelle Interaktion sowie der Archäologie von Schriftsystemen widmet. Nachdem er sich in seiner Doktorarbeit mit dem Thema ‘Social Change in “Phoenicia” in the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age transition’ vom 13. bis 10. Jh. v.Chr. beschäftigt hat, behandelt sein aktuelles Forschungsprojekt den Kontext des Schreibens im Stadtstaat Ugarit und besonders der Entwicklung und Verwendung der von dort stammenden alphabetischen Keilschrift in der späten Bronzezeit. Philips Arbeitsschwerpunkt lässt sich leicht in dem bemerkenswerten Artikel wiederfinden, den er ursprünglich für seinen eigenen Blog Ancients Worlds verfasst hat, mir aber freundlicherweise auch für meinen Blog zur Verfügung stellte. Zum ursprünglichen Artikel kommt Ihr hier.

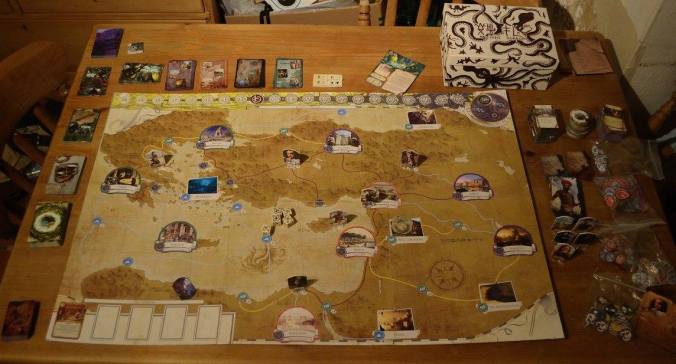

I wrote recently about the excellent Lovecraftian board game Eldritch Horror. That post was actually something of a preliminary to this one. You see, for the last several months I’ve been working on my own version of Eldritch Horror, set in the East Mediterranean Bronze Age.

Earlier this year, my friend and colleague Anna Judson called us together to play something else – her excellent Mycenopoly: an Aegean Bronze Age themed version of Monopoly, complete with barter system and utilities such as textile works and the ability to build megara instead of hotels. I highly recommend checking out her own blog about it, which went a bit viral, and deservedly so. Apart from having an excellent time with Mycenopoly, the evening left me wondering if it would be possible to do something similar for the game we most often play together, Eldritch Horror.

For those who haven’t read my original post, a quick recap: Eldritch Horror is a co-operative game in which players guide investigators round the world, fighting monsters and having uncanny encounters as they battle to prevent the world-ending advent of some great cosmic horror – Cthulhu or one of his pals. That game is set in the 20s-30s, and that’s a pretty cool setting. But the Bronze Age? That could be amazing! Who wouldn’t want to fight Lovecraftian monsters in the East Mediterranean c.1200 BC? The setting, after all, is perfect – it’s a time as like an apocalypse as the world has ever known, when the great civilisations of the Mediterranean world faltered or collapsed for reasons that remain almost entirely mysterious. The Mycenaean palaces were burned to the ground, accidentally firing their precious archives of Linear B tablets; the Hittite Empire suffered famine and fragmentation; Ugarit was razed to the ground and even the mighty Egyptian New Kingdom ended amid riots, food shortages and political partition. Texts from the period alluding to ‘watchers watching the coasts’ and ‘people who live on boats’ have prompted all manner of fanciful theories about great wars and migrations, of invasions by Sea Peoples. I’m not going to go into this in depth now, but suffice to say I’m very sceptical of a lot of these invasion theories, and the reality was a lot more complex. But I don’t believe in the monsters either, and mashing together a consciously lurid imagining of the end of the Bronze Age creates a realm of fun possibilities.

For those who haven’t read my original post, a quick recap: Eldritch Horror is a co-operative game in which players guide investigators round the world, fighting monsters and having uncanny encounters as they battle to prevent the world-ending advent of some great cosmic horror – Cthulhu or one of his pals. That game is set in the 20s-30s, and that’s a pretty cool setting. But the Bronze Age? That could be amazing! Who wouldn’t want to fight Lovecraftian monsters in the East Mediterranean c.1200 BC? The setting, after all, is perfect – it’s a time as like an apocalypse as the world has ever known, when the great civilisations of the Mediterranean world faltered or collapsed for reasons that remain almost entirely mysterious. The Mycenaean palaces were burned to the ground, accidentally firing their precious archives of Linear B tablets; the Hittite Empire suffered famine and fragmentation; Ugarit was razed to the ground and even the mighty Egyptian New Kingdom ended amid riots, food shortages and political partition. Texts from the period alluding to ‘watchers watching the coasts’ and ‘people who live on boats’ have prompted all manner of fanciful theories about great wars and migrations, of invasions by Sea Peoples. I’m not going to go into this in depth now, but suffice to say I’m very sceptical of a lot of these invasion theories, and the reality was a lot more complex. But I don’t believe in the monsters either, and mashing together a consciously lurid imagining of the end of the Bronze Age creates a realm of fun possibilities.

Designing the game

The challenge is that Eldritch Horror is an extremely sprawling and complicated game. The rules are fairly straightforward once you master them, but the sheer amount of stuff it involves is daunting. In particular, there’s an abundance of different cards, almost all of which are extremely text-heavy, as befits a narrative-focused game. As the original game is set in the 20s or 30s, all of these would need to be rewritten for a Bronze Age setting. The game’s also stuffed with artwork, much of which would need to be replaced. This would be a lengthy job, and it’s one that’s taken me since June. The text files I’ve created run to tens of thousands of words and I sent off image files for the fronts and backs of nearly 200 cards to the printers. Even that’s the bare minimum the game can work with – Eldritch Horror becomes a lot less repetitious when you add in its expansion packs, but I haven’t attempted to replicate the content from them. Not yet…

An early decision I had to make was what version of the Bronze Age I wanted to set this in. It was never my intention to create something as reflective of the real world as Mycenopoly – given that any version of Eldritch Horror would be stuffed to the brim with monsters, cultists and magic, there didn’t seem much point, and I wanted to keep the source game’s pulpy feel. On the other hand, I was clear I wanted this to be set in something resembling the actual Late Bronze Age, not in a vaguely defined ‘Greek mythology’ or its Near Eastern equivalent. What I eventually went for is something I would like to think of as Bronzepunk (after Steampunk etc.). While nominally set in a real Bronze Age where technology, society and culture are depicted more or less realistically (there are lots of references to the exchange of diplomatic tablets between the region’s Great Kings, for example), the game is happy to pick and choose, remix, and play a bit fast and loose with chronology for the sake of telling a fun, cool adventure story or subverting how we conventionally think about the period. So, for example, Akhenaten – Egypt’s monotheistic heretic pharaoh – is present a couple of centuries after he really lived because he fits the Lovecraftian tone too well to leave out.

Crafting a cast

Eldritch Horror’s Investigators are pre-defined characters with their own artwork, abilities and back-stories. For Ancient Horror I based as many of my Investigators as possible on actual known Bronze Age people, trying to assemble an eclectic bunch in terms of gender, culture and background, while unashamedly focusing on my own and my friends’ favourites. As well as Akhenaten, there’s Karpathia, the trouble-making Pylian Keybearer; Puduhepa, the powerful Hittite queen; Piyamaradu, the rebel from Asia Minor; Phugegwrins the scribe; Shipitba’al the Ugaritian merchant (not an Asterix character, though he sounds like he should be), and so on. For other characters, I used real Bronze Age names but attached them to invented characters, such as Tuzo, my Minoan textile-worker or Qaqarys the mercenary. In a conscious reaction against some of Lovecraft’s more unpleasant characteristics, and the often rather stereotypical depiction of non-white characters in Eldritch Horror, I did my best to make the cast diverse and to present them in the artwork as genuinely Mediterranean- or Near-Eastern looking, rather than blandly Caucasian. The cards that control what befalls characters in the game don’t distinguish on the basis of gender, age or class, so things like same-sex relationships are perfectly possible – indeed likely – in the game. Anyone can be a hero, anyone can be a liability.

Another thing I wanted to do with the characters involved their back-stories, and this was the one area where I introduced a new game mechanic. In Eldritch Horror, although characters’ cards tell you their back-stories or the personal missions that launched them on their battle against the cosmic horrors, these don’t actually come into play in the game itself. A character looking for redemption will never find it; one seeking a lost love one will never be reunited. In Ancient Horror every character has a unique Personal Quest which can be triggered by chance during the game. This ties into their back-story and offers some potential resolution. The rewards can be big, but so are the risks; do you put the fight against evil on hold while you pursue a dangerous mission of self-gratification? Rather than the chance dice-rolls that determine the outcome of most adventures in the game, these quests often rely on the player to make a moral or tactical choice. The down-side is that each quest can only be played once before players learn what will transpire, but given that there are more potential characters than players, and the Personal Quests are not guaranteed to occur in any given play-through, I’m hoping that they’ll still allow us to have a couple of games at least before things start to repeat.

Playing the game

I’d hoped we could play the game at Hallowe’en, but there were so many cards that the only practical option was to have them professionally printed, and they didn’t arrive until a few days too late. Busy schedules intervened and it wasn’t until yesterday that we finally managed to sit down with the shiny new Ancient Horror. I took advantage of the delay to hand-paint a box for it. I’m rather happy with it.

For our first game we faced off against Dagon, the natural choice for a villain since he is both a Lovecraftian monster and a major deity worshipped in the Bronze Age Levant (especially in Ugarit, where his is one of the two large temples on the city’s acropolis, although I started working on this long before I had any inkling how significant Ugarit was about to become for me). Our starting Investigators were Phugegwrins the Mycenaean scribe, Puduhepa the Hittite queen, Kutuqano the bull-leaper, Piyamaradu the Anatolian rebel, Karpathia the Pylian Keybearer and Nabua the Mesopotamian astrologer.

Over the course of the game there was drama, horror and comedy. Puduhepa, the brilliant diplomat and politician, revealed herself as a compulsive hoarder of weaponry; in her absence, Piyamaradu took advantage of an opening and sacked Hattuša, removing its shops and facilities permanently from the game. Later on, Puduhepa was forced to sacrifice one of the other players to a terrible fate and wasted no time in using the knife on Piyamaradu. Phugegwrins (a brooding detective as well as a scribe and butler) faced down his nemesis, the Knossos serial-killer, but accidentally got a child killed in the final confrontation. Kutuqano went insane while fighting the Great Deep One and was replaced by Shipitba’al, whose main achievement was drunkenly setting off on a quest to find a stranger a centaur bride, despite being fairly sure centaurs do not exist.

In the end we defeated Dagon – only just – but the toll was high. Hattuša in ruins, two Investigators insane and one devoured by something unholy. Many of the survivors were carrying multiple injuries, illnesses or curses.

I can’t claim it was as educational as Mycenopoly, but we had lots of fun, and there’s still plenty of the game left to discover – new surprises and new monsters to fight.

And at some point I might make some expansion material.

EDIT – I’ve written a follow-up post about how I produced the map on the game-board, if that’s something that interests you.

Do you have any favourite Bronze Age monsters, characters or macabre stories that you think I should include in future material for the game? If so, let me know in the comments!

I should also say that because Eldritch Horror is a commercially-created game to which I don’t own the rights, Ancient Horror can only ever be for my own use – I’m afraid it can never be distributed, sold or made available in any way. But I’m more than happy to play it with anyone interested in the Cambridge area.

[This article has been published first on Ancient Worlds.]

- Stephen Kings SHINING. Analysen, Hintergründe zu den Filmen & Romanen. Buchrezension von Stefan Preis - 21. September 2023

- A Nightmare on Elm Street – Freddy Krueger als antiker Vampir (Stefan Preis) - 1. September 2023

- Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher Geschichte(n) in Peter S. Beagles „Das Letzte Einhorn“ - 16. Juli 2023

Schreibe einen Kommentar