A New Way to “Engage”? Gilgamesh in Star Trek … and Beyond (Gastbeitrag von Louise M. Pryke)

[The English text begins after a short introduction in German]

Louise M. Pryke lehrt an der Macquarie University Sidney Sprachen und Literatur des antiken Israels. In ihrer Doktorarbeit untersuchte sie die diplomatische Korrespondenz zwischen den Pharaonen des Neuen Reiches mit ihren Repräsentanten in der Levante. Zu ihren Forschungsinteressen zählen die Sprachen und Literatur des antiken Israels, altorientalische Religionen, Mythen, Epen und Erzählungen sowie die hebräische Bibel, die Göttin Ishtar, die Armana-Briefe und schließlich antike Diplomatie und Kommunikation. Aufmerksam wurde ich auf Louise Pryke durch ihre Studien zu Gilgamesch, in deren Rahmen sie sich auch mit der Rezeption des Königs von Uruk beschäftigt. In Kürze wird sie eine Monographie zu Gilgamesch veröffentlichen, auf die ich mich schon sehr freue. Heute berichtet uns Louise Pryke von Gilgamesch in Star Trek und darüber hinaus:

„Gilgamesh is the world’s first hero of ancient epic literature. His story is told in the Epic of Gilgamesh, a literary masterpiece from ancient Mesopotamia. The Epic centres on the Gilgamesh’s legendary journey from his home in Uruk to the very edges of the known world—and beyond. During his travels, Gilgamesh battles with deities and monsters, treads new pathways, and discovers riches hidden in secret places.

Gilgamesh, with his heroic strength and superhuman deeds, can only be described in superlative terms. Yet, despite the exceptional quality of Gilgamesh’s achievements and characteristics, he remains a very human character, one who experiences the same heartbreaks, limitations, and simple pleasures that shape the universal quality of the human condition. Gilgamesh’s epic adventuring, coupled with his human vulnerability, make him a complex and fascinating hero of the ancient world.

Gilgamesh is undoubtedly less widely known in the modern day than many Classical heroes, yet his story is one that has been embraced by audiences in the present day—a phenomenon known as “Gilgameshiana.” In diverse works such as televisions’ Star Trek and comic books, the story of Gilgamesh is retold, and the Epic’s characters are adapted for new contexts. While Gilgamesh has only been widely available for use in modern artistic works since the end of the second World War, the connection between the science fiction and fantasy genres and Gilgamesh may be much older.

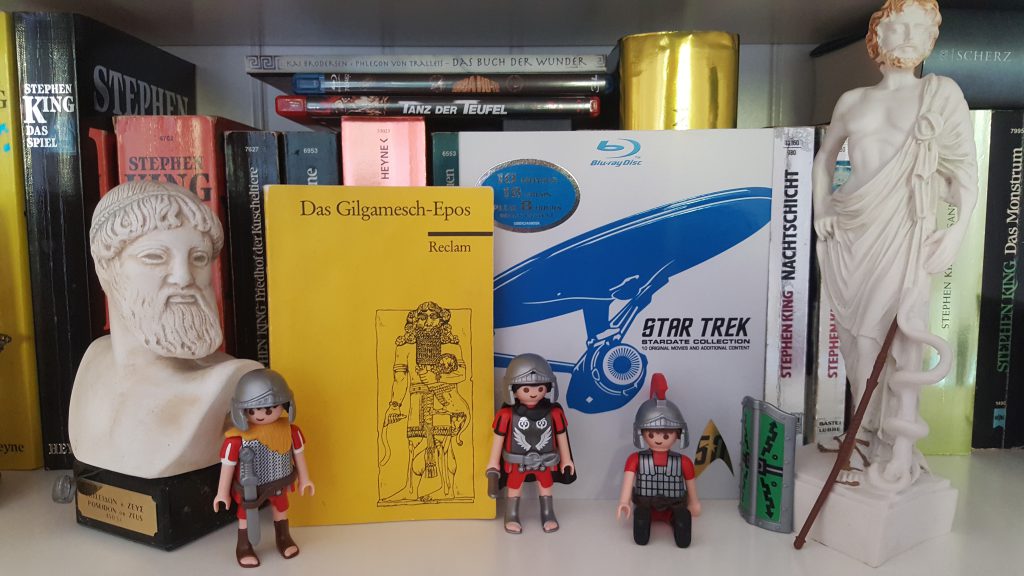

Photo: Michael Kleu

Gilgamesh, science fiction, and fantasy

The genre which modern audiences would recognise as science fiction emerged around the time of the nineteenth century CE, propelled by the social and cultural changes of the industrial revolution. The works of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells pioneered the two major modes of science fiction that have dominated the genre from that time; these being the “hard/didactic” and “speculative/fantastic” respectively (Evans, 2009: 13).

It has been argued that the literary tradition of science fiction and fantasy has much more ancient origins. Scholars such as Brian Aldiss have suggested that the fantastical elements of many ancient literary texts permit their inclusion in the “canon” of works in the genre of science fiction and fantasy. The supernatural and fantastical elements of the Gilgamesh Epic have earned it a place in the discourse over the origins and development of science and fiction. In 1972, the French science fiction writer and scholar Pierre Versins noted that the search for eternal life in Gilgamesh made it the earliest known work of science fiction (Versins, 1972). This view was also endorsed by the American author, Lester del Rey (1980).

Gilgamesh’s place at the beginning of what would later be known as science fiction has been explored by Gunn, who noted that “Gilgamesh’s concerns are those of science fiction” (2002: xii). Gunn observed the foreshadowing in Gilgamesh of elements typical to later science fiction, such as a partly-divine hero, the attempts at control over elements, the heroic habit of saving people, and even an appreciation of technology in the walls of Uruk (1977: 1.xi, xiii).

This connection was noted in several books in the first half of the 20th century, most famously in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949). Campbell uses the second-half of Gilgamesh’s adventure for an example of an elixir quest—quests which have lost none of their appeal in over four millennia (Campbell, 1949).

Possible representation of Gilgamesh, Louvre

Gilgamesh meets Star Trek

Gilgamesh’s willingness to boldly go where no Mesopotamian has gone before makes him a good fit for a television series set in space—the final frontier. The hero’s story is used didactically by Captain Jean-Luc Picard (played by Patrick Stewart) in a fifth season episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1991), titled “Darmok.” The episode thoughtfully explores the themes of the Epic and the power of narrative.

The aliens who Picard encounters in the episode have an unusual means of communication, requiring the decoding of imagery. This mode of alien communication provides scope for consideration of the importance of narrative and context for drawing meaning from imagery. The lack of context for the aliens’ allegories creates barriers to understanding, but the desire to communicate and connect, and the universal aspects of the shared stories, allow for a bond to be formed.

The power of story-telling is further emphasised as the captain of the Enterprise and the alien commander, Captain Dathon (Paul Winfield—who also played a Star Fleet commanding officer in Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan) exchange details from the epic narratives indigenous to their individual cultures. Picard recounts the story of Gilgamesh, beginning by remarking on its extreme antiquity (even more notable given the episode’s 24th century setting).

The epic narrative from the alien culture shows some mirroring of aspects of Gilgamesh; the story features two individuals, perhaps rivals, who travel to a distant setting and face a “beast,” becoming allies in the process and inseparable companions. The episode demonstrates how both cultures frame and make sense of their current situation through mythological tropes. In this way, the importance of understanding the stories of a culture to gain an insight into an alien worldview is emphasised.

Events in the episode’s narrative also show some cross-over with Gilgamesh, as the two leaders, who were formerly adversaries, unite to fight a powerful creature. The battle results in the death of the alien captain, and Picard both mourns and commemorates his lost friend.

Picard clearly identifies himself with Gilgamesh, and the alien Dathon with Enkidu, and by applying the story to his personal circumstances, the audience gets a clearer view of Picard’s inner life. The story concludes with Picard reacquainting himself with the Homeric hymns, with a renewed appreciation for the timeless value of mythology, and the narrative riches of the past.

A home in the stars

Gilgamesh’s ventures into space do not end with Star Trek. The largest moon of the planet Jupiter has a basin on its crust named for the ancient hero. Gilgamesh’s mighty opponent from his epic story, the giant Bull of Heaven, also has a lasting home in the night sky, having an enduring association with the constellation now known as Taurus.

From this brief discussion of the reception of the world’s oldest epic, it is possible to see the diverse ways that powerful stories continue to resonate. Characters and stories from the ancient world are continually reinvented to meet new audiences over the millennia, and even echo back at us from the furthest reaches of the stars.“

Louise M. Pryke

Recomended reads (by Michael Kleu)

Classical Trek: Darmok (Article by Daniel B. Unruh)

Marvel meets Mesopotamia: How modern comics preserve ancient myths (article by Louise Pryke)

Review of Jens Harder’s Gilgamesch by Nerd mit Nadel (Ariane)

Review of Jens Harder’s Gilgamesch by Booknapping (Sandra)

… and even more classical reception in Star Trek …

- Doctor Who trifft Sokrates und Platon im antiken Athen: The Chains of Olympus (Comic, 2011–2012) - 31. August 2024

- Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher Geschichte(n) in Peter S. Beagles „Das Letzte Einhorn“ - 16. Juli 2023

- Römische Arenen und Wilder Westen: Jasmin Jülichers „Stadt der Asche“ - 4. Oktober 2022

Hallo zusammen!

Mit dem Gilgamesch habe ich mich im Rahmen meiner Bibelstudien auch beschäftigt. Kurz vielleicht vorweg: mit Picard mag ich ihn so gar nicht gleichsetzen. Zu Anfang seiner Abenteuer ähnelt er eher dem Kirk aus dem Spiegeluniversum (Mirror Mirror), als der „Wilde Mann“, der sich nimmt, was er will. Erst als er Enkidu trifft und ihn im Kampf gegeneinander zu respektieren beginnt, ändern sich seine Ziele ein wenig.

Persönlich halte ich das Epos für einen, mit phantastischen Elementen angereicherten, Tatsachenbericht. Ob Enkidu nun ein einzelner Steppenbewohner war oder vielleicht Anführer eines Stammes, der im Gegensatz zu den Städtern eine als tierisch empfundene Lebensweise pflegte, bleibt natürlich offen.

Es ist gut vorstellbar, dass sie als Verbündete einen Raubzug unternahmen, um Holz zu besorgen. Das scheint übrigens nicht im Libanon gewesen zu sein, sondern im Osten, vielleicht in Elam.

Der Text lässt auch vermuten, dass Gilgamesch später in der Gegenrichtung, am Schwarzen Meer, einen Überlebenden einer/der Flut aufsuchte, der ihn aber abblitzen ließ. Fun Fact am Rand: Gilgamesch trifft vor seiner Überfahrt die „Schankwirtin“ Siduri, vielleicht die Betreiberin eines Handelspostens. Bei Troja soll es einen Ort geben namens Sivritepe. Das ist natürlich kein Beweis, aber eines von mehreren Indizien.

Das sind natürlich auch eine Menge „vielleichts“, was aber kein Wunder ist bei einem Text, der mindestens 4000 Jahre auf dem Buckel hat, mehrfach überarbeitet wurde, und nur in Fragmenten aus dem Wüstensand gebuddelt wurde.

Und selbst wenn es nur eine Geschichte war, auch diese muss eine Grundlage, einen realen Hintergrund gehabt haben, wie wir ihn auch z. B. bei der Ilias vermuten können. Auch unsere heutige Gegenwartsliteratur spiegelt ja reale Erfahrungen wider, selbst in einem „phantastischen“ Setting.

„Auch unsere heutige Gegenwartsliteratur spiegelt ja reale Erfahrungen wider, selbst in einem „phantastischen“ Setting.“

Ja, das sehe ich auch so. Darum nutzen wir Ilias und Odyssee ja auch in einem gewissen Rahmen als historische Quellen. Auch wenn die Story zumindest teilweise erfunden ist, spiegeln sich ja Erfahrungen aus der realen Welt des oder der Autoren darin wieder.

Richtig spannend fand ich in diesem Kontext den folgenden Artikel:

https://theconversation.com/the-worlds-oldest-story-astronomers-say-global-myths-about-seven-sisters-stars-may-reach-back-100-000-years-151568

Wenn das zutreffen sollte, wäre das so richtig, richtig krass.