The Monster in the Labyrinth – Finding Your Way In and Out of „Inception“

“… often, when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream.”[1]

Introduction

Classical antiquity has long provided its posterity with a treasure trove of magnificent and unbelievable narratives, characters, myths, and creatures free for the taking. The myths, characters, and narratives can be seen in everything from modern art and literature, to films and advertisements and are thus used for aesthetic, entertainment and economic incentives alike. Sometimes the classical references are obvious, and the modern use serves as a mere retelling of the ancient sources.

Other times the references are more obscure meaning that only some recipients, and even some writers or producers, will be conscious of the possible intertextuality. Because, while classical allusions may be present in modern books or films, certain references might have become an unconscious part of our collective memory, which means we cannot be sure the writer or producer put the references there deliberately.

One of these more obscure retellings of an ancient myth can be seen in the film Inception that premiered in 2010. On the surface, the film has nothing to do with classical Greek myths, but digging a bit deeper, substantial elements from the myths surrounding Theseus and that of Theseus and the Minotaur specifically can be traced. Therefore, the goal in this article is to determine whether the similarities between the two narratives were applied consciously in the new context or not and not least why.

Material and methodology

The key to unlocking the questions above is running the film Inception and the myth of Theseus through modern theoretical approaches like uses of history and reception theory. The fields both deal with how certain parts of history are used and with what purpose, and yet they approach the topic from two different viewpoints. Having dealt with the two theories, their similarities and differences extensively before,[2] I will not do so in this article. Rather, the template created in previous articles will be reused as it has served other analyses well in the past.

Firstly, an examination of the myth about Theseus and the Minotaur is conducted in “You are here” thereby establishing a historical and literary starting point. Secondly, the paragraph “Follow the ball of yarn” looks at how this particular myth spread its threads to several other works be it literary, artistic, or cinematic. Finally, the myths and references are compared to the film Inception looking at the producer’s preconditions for knowing about the ancient starting point, the similarities and differences between the works, when the work premiered and why, and eventually whether the use of the ancient source in the new context has had any effects on the audience or not.

On a linguistic note, the terms “labyrinth” and “maze” will be used interchangeably, as I do not seek to distinguish between the various interpretations of labyrinths versus mazes and them being either unicursal or multicursal.

Research overview

Several short blog-entries about the use of the Theseus myth in Inception exist online, and more elaborate analyses on the film in general can also be found. Yet, I have not been able to find other thoroughgoing analyses of the topic chosen for this investigation. In the following I will mention some of the papers or books I have encountered which deal with Inception or the myth of Theseus therein in various ways.

“Dreaming Other Worlds: Commodity Culture, Mass Desire, and the Ideology of Inception” by Martin Danyluk addresses how the film, in spite of its thoughts on technological ingenuity, sticks to basic social, economic, and political constructions. In this way, albeit delivering a well written and articulate article about Inception and the themes within, Danyluk does not comment on the classical references in Inception.

In “Nolan’s Immersive Allegories of Filmmaking in Inception and The Prestige” Jonathan R. Olson comments on how Inception can be seen as an allegory of filmmaking – something Nolan himself has commented on as well.[3] The same goes for Devin Faraci’s article “Never Wake Up: The Meaning and Secret of Inception”.

While these texts do not mention a connection to a mythical past, other chapters taken from the same book as Olson’s chapter do – although only in the passing. In “’The dream has become their reality’: Infinite Regression in Christopher Nolan’s Memento and Inception” Lisa K. Perdigao writes: “With an allusive name signifying her ability to navigate a complex labyrinth, the new architect Ariadne figures out the story of Cobb’s traumatic past.”.[4] Sorcha Ní Fhlainn also calls Ariadne “aptly-named”[5] in the chapter “’You keep telling yourself what you know, but what do you believe?’: Cultural Spin, Puzzle Films and Mind Games in the Cinema of Christopher Nolan”, but both of these chapters leave the classical references at that.

The most direct reference is featured in Jacqueline Furby’s “About Time Too: From Interstellar to Following, Christopher Nolan’s Continuing Preoccupation With Time-Travel”. Herein Furby writes: “… names are clearly important in Nolan’s films, and it is therefore significant that Ariadne, who shares her name with the character of Greek mythology who leads the hero Theseus out of the labyrinth after he has slain the Minotaur, is the one to help Cobb to escape his own emotional maze.”[6] But again, no further details on the myth and its metamorphosis into a modern film is mentioned – let alone why and what the connection means.

Todd McGowan too comments on Ariadne’s name in his book Fictional Christopher Nolan, but does not elaborate on the mythical connection as such. He solely addresses the importance of names in Inception and that Ariadne is so-named in order to make the audience trust her.[7] But can the name be deemed trustworthy in itself, if we consider the possibility that the audience might not be familiar with the ancient myth? In that case, the name only appears trustworthy to those in the know, which means that the character more than the name is what makes Ariadne trustworthy to the rest.

While philosophising over Inception and whether or not we are dreaming in this exact moment, David Kyle Johnson mentions Plato and The Allegory of the Cave in connection to the film.[8] Even though Johnson does not compare the myth of Theseus to Inception, he still sees similarities between other writers and narratives from classical antiquity – similarities which to me seem meaningful.

Albeit short, this research overview shows how researchers commonly have chosen to focus on other aspects of Inception than the references to myths from classical antiquity within. Some researchers mention Ariadne and her name’s connection to Theseus and his endeavours on Crete but refrain from digging deeper into why Nolan chose this particular name. This, and how the myth of Theseus and Inception are otherwise connected, is what I seek to accomplish with this article.

“You are here”

Apparently, the myths surrounding Theseus evolved and expanded over time – much like many other Greek myths. It seems that Theseus, a mythical king of Athens, started out as a local hero from the northern part of Attica, and then later functioned as a Heracles-type figure who was used as an example of a king skilled enough to unify the many city states in Attica.[9] Various myths are connected to Theseus, but the one most important for the analysis of Inception is that of Theseus and the Minotaur.

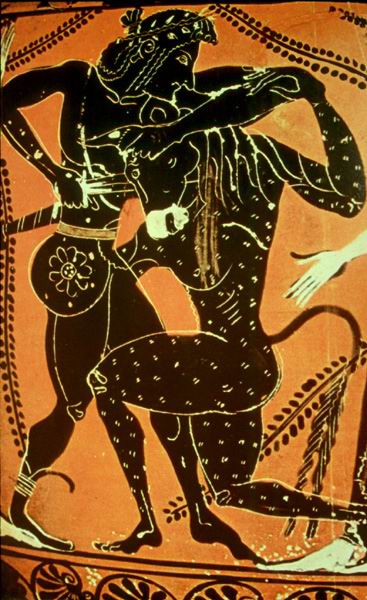

The Minotaur was a half-man half-bull creature born after a bull meant as sacrifice for Poseidon mated with king Minos’ wife Pasiphae.[10] King Minos of Crete kept the Minotaur in a labyrinth designed by the skilled craftsman Daedalus, and every year seven boys and seven girls were sent from Athens as sacrifice to the incarcerated creature. The hero Theseus went to Knossos with the intent of liberating the Athenians of this burden, entered the labyrinth, and killed the Minotaur.

He managed to find his way back out because Minos’ daughter Ariadne, who had fallen in love with him, gave him a ball of yarn to unravel on his way.[11] He followed the thread back and took Ariadne with him, but then left her on the island of Naxos before returning to Athens himself. Here his father Aegeus threw himself to his death from the Athenian Acropolis, as Theseus had forgotten to fly white sails as agreed had he survived. The black sails signalled his death thereby prompting Aegeus’ death and Theseus’ succession as king of Athens.[12]

But the fates of Minos’ family and Theseus would stay interwoven deeming his troubles far from over. After Theseus’ victory over the Minotaur he had a son named Hippolytos whose mother was an amazon. Theseus then married Ariadne’s sister Phaedra who, like her mother, was struck by a forbidden desire – she fell in love with her stepson. All ended tragically when Phaedra killed herself and Theseus cursed Hippolytos after being told that he was the one who desired Phaedra and not the other way around.[13]

Obviously, Theseus was portrayed as a flawed hero; leaving his girlfriend behind on a beach, not respecting the agreement made with his father subsequently causing his death, and cursing his own son before being presented with all the facts leading to the death of the same. Whether the mythical hero and king of Athens did exit we cannot know, but it is believed that the myth of the Minotaur is connected to the ancient Cretan sport of bull-leaping where young men would jump over bulls in imaginative ways,[14] in this way connecting myth and reality. But did the myths surrounding Theseus get an afterlife themselves, and have they left their impressions somewhere?

Follow the ball of yarn

To most, it should not come as a surprise that Theseus’ ball of yarn has spun its threads throughout history, in multiple countries, and across various media. Even in classical antiquity Theseus and his destiny provided material for retellings. A part of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (published ca. 8 A.D.)[15] refers the tale of Phaedra and Hippolytos as well as the battle between Theseus and the Minotaur.[16] Seneca’s Phaedra (performed 50 A.D.)[17] also revolves around the tragical fate of Phaedra and Hippolytos. But none treated the myths surrounding Theseus as thoroughly as Plutarch (lived ca. 45-120 A.D.) – a Greek-Roman writer, historian, and priest whose main works consist of biographies and philosophical essays. One of these, Theseus, tells the life story of Theseus from his birth, over the discovery of his true identity, to the tale of Ariadne, the labyrinth, and the Minotaur as well as a short reference to Hippolytos.[18] Fast forwarding, writings from classical antiquity flourished during the renaissance, and Shakespeare among others was heavily inspired by Plutarch’s Lives.[19]

Thusly oth Chaucer and Shakespeare whose writings, as we will see in the paragraph “Inception” presumably played a part in the curriculum studied by Nolan during his studies, treated the myth of Theseus; Chaucer in The Knight’s Tale (published 1400)[20] where Theseus plays the part as duke of Athens, and Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (written ca. 1595)[21] and The Two Noble Kinsmen (published 1634)[22] where Theseus likewise is featured as the duke of Athens.[23] In addition, we find the tale of Theseus, Phaedra and Hippolytos in France recreated in the tragedy Phèdre (first performed 1677)[24] written by Jean Racine.

But where the narratives from classical antiquity and the tragedy of Racine focus on the relationship between Theseus, Phaedra, and Hippolytos, The Knight’s Tale, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Two Noble Kinsmen feature Hippolyta – Hippolytos’ legendary mother who was queen of the amazons as the wife of Theseus. Apart from Ovid’s Metamorphoses only The Knight’s Tale mentions the Minotaur,[25] which means all the interpretations mentioned above add or omit the elements deemed necessary for the dissemination of the plot.[26]

This may seem odd, but myths in classical antiquity were just as fluent, and the examples chosen here thus simply underline their position in a long-lasting tradition. More recent examples support this statement as British comedian Tony Robinson in collaboration with Richard Curtis wrote the book Theseus: The King Who Killed the Minotaur (1988) – a humorous retelling of the classical myths aimed at a young audience.

Author Suzanne Collins who wrote The Hunger Games trilogy (2008-2010) has stated that she, among other things, was inspired by the myth of Theseus for the trilogy’s storyline[27] – a young girl questioning and challenging the existing practice of annually sacrificing a boy and a girl in the name of entertainment. Finally, the film Immortals (2011) features Theseus as he fights the evil king Hyperion, who wishes to free the Titans long bound to the depths of Tartaros. Theseus falls in love with the oracle Phaedra, and even fights a Minotaur in a labyrinth at one point.[28]

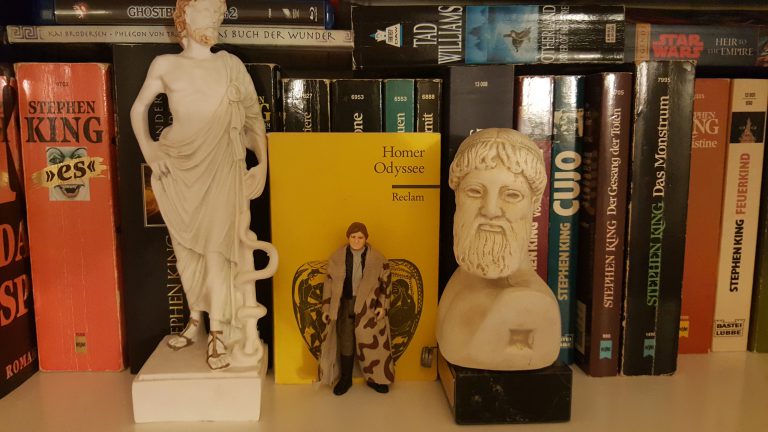

Therefore, the strings of the ancient myth is connected to numerous adaptations or hybrid-works spanning literary, visual, and even artistic examples as shown in the pictures above.[29] Furthermore, the myth has been reworked to function as both comedy and tragedy depending on the media and the audience. This underlines the myth’s popularity as well as its great appeal to young and old alike through the centuries.

Inception

Introduction

The sci-fi thriller Inception premiered in 2010 with a plot centred around the thief Dominick Cobb and his efforts to redeem himself via one last mission that could ensure a reunion with his children. But Cobb is no ordinary thief – he steals corporate secrets from high-profiled businessmen from their subconscious while they are sleeping. Besides this, he is wanted for murder and thus, he is wanted internationally, which is why he has been separated from his children.

The last mission differs from those that have gone before, as the plan is to plant an idea rather than steal one, in this way hopefully affecting events in real life. For the plan to work it is crucial that the dreamer remains unconscious of being manipulated while dreaming – that is he cannot become aware of the dream being just that. It must seem as if the idea came from himself rather than from an outside force; he needs to believe that the things Cobb and his team show him represent the truth. Meticulous planning and cunning are required from Cobb and his team in order to solve the task and avoid the dangerous obstacles in their way.

Who is the user and is the use intentional?

The film was both written and directed by Christopher Nolan, who already began experimenting with the art of filmmaking at the age of seven.[30] Nolan studied English Literature at University College London while shooting films at the university’s film society, and like this, the elements of English literature and filmmaking were intertwined. The university’s current description of the BA in English states that it: “…provides a historically-based overview of literature from the seventh century to the present day, together with opportunities to specialise in particular periods of literature, in modern English language, and in thematic areas.”[31]

In this way, the degree ensures the students’ ability to tailor their education according to their individual interests. If we assume that the current description mirrors that of the time when Nolan studied English Literature, this means that Nolan had the opportunity to combine his interest in filmmaking with his favourite narratives of the past. The BA is constructed so that: “The first year of the English BA acts as a foundation for the two following years, covering major narrative texts from the Renaissance to the present, an introduction to Old and Middle English, the study of critical method, and the study of intellectual and cultural sources (texts which influence English literature but which are not in themselves necessarily classified as such).”[32]

This suggests the students could be studying texts from classical antiquity in order to trace their influence on later English literature. Consequently, this seems a not only possible, but probable source of Nolan’s knowledge about classical antiquity, its myths, and characters – again assuming that the general framework surrounding the BA in English Literature has remained more or less the same. Looking at the description above this seems likely, as the wording ensures a broad and general rather than specific approach to certain works or writers. And yet, specific works or writers within any field will be considered canonical and therefore compulsory. This becomes evident when looking through the content of specific courses connected to the BA in English Literature at UCL.

Even though the English Renaissance, a period mentioned above as a focus of study, began later than its Italian counterpart, it still meant a rebirth of the classical world and its ideals – especially in English literature. This is clearly seen in the works of William Shakespeare who drew heavily on Greek and Roman mythology and history.[33]

In fact, studying Shakespeare’s writings is part of a compulsory curriculum at the university: “In the second and third year you will study compulsory modules on Chaucer and Shakespeare […]”[34] This means that Nolan was most likely introduced not only to Shakespeare’s plays, but also to the writings of Geoffrey Chaucer, who likewise was influenced by Greek mythology and Roman writers like Ovid.[35] But just because texts from classical antiquity and teachings about their influence on English Renaissance literature presumably formed, and still form, a part of this specific curriculum, we cannot be sure it affected Nolan in any way.

Yet Inception holds several references to classical antiquity – most obviously Ariadne – a young woman in Cobb’s team who is put in charge of creating the labyrinth dreamscapes they need in order to fool their victims. The mazes contain challenges, or monsters if you will, but particularly one causes Cobb trouble. Furthermore, Cobb makes a reference to the concept Catharsis (κάθαρσις)[36] – a concept addressed by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle in his Poetics.[37]

The concept is used as a means of explaining the closure and sense of fulfilment we experience when watching a play or a film, while often lacking this fulfilment in real life. Additionally, Nolan has stated that the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey had an influence on him[38] – a film set in space but built upon Homer’s The Odyssey. Nolan’s understanding of and attraction to this film as well as his studies adds to our assumption that Nolan along with a probable general collective consciousness, to some degree, possesses a knowledge of myths, characters, and writers from classical antiquity.

Therefore, it seems likely that Nolan placed the classical references in general and the specific allusions to Theseus, the labyrinth and the Minotaur in Inception deliberately, but how closely does the film, its characters, and its story resemble the ancient myth?

How does the form, content/scenes – including additions or omissions – and characters of the new work relate to the source and why?

The form of the two narratives differ in the sense that the stories of Theseus, his family, and the Minotaur started as orally transmitted myths which were then written down by later poets and writers. Inception started as a written narrative meant for the big screen, which means the writer had the opportunity to consider other courses of action and other effects that would do well visually. The change in media offers both possibilities and difficulties, because while computer technology provides ways of portraying the otherwise impossible in actions, characters, and creatures alike, the trick is to know where and when to stop.

Watching a film at the theatre can be an overwhelming experience, and if the narrative appears too imaginative or unrealistic the result is an unengaged audience. Yet, both tales excel in the use of believable characters and real-life topography making the storylines convincing and credible in spite of their fantastic content.[39] The similarities between the myth of Theseus and Inception are constituted by how they both contain wild thought experiments, and by how both show us the consequences of experiments gone wrong.

Furthermore, the trick for the ancient singers or writers consisted in painting the gory details as vividly as possible as they had no other way of doing so, whereas the details we cannot see directly on screen often have a larger effect on the audience as people’s own imagination is engaged.[40] Both then speak to the mind of the listener, reader, or viewer, showing us that our own imagination, dreams, and fears can be activated as a source of narration – thus making the story more plausible as the audience creates part of the narrative themselves.

The Cambridge English Dictionary states that the word “Inception” is synonymous with the words beginning or origin.[41] Much the same goes for the site etymonline which deals with the etymology of words. Here it is stated that “Inception” is derived from the Latin “Inceptionem” meaning a beginning or undertaking but also that the latter part of the word “incipere” means to take or seize.[42] Thusly, the word connotes both the beginning of something, maybe the inauguration of a new tradition, and to take or seize something.

Looking back at the myth of Theseus, he is the first to question and challenge the unusual tradition of sacrificing seven boys and girls to the Minotaur – accordingly challenging the Minotaur as well. Hence, he takes initiative as well as risks and ends up taking the life of the Minotaur. Likewise, Cobb is the first to experiment with the concept of inception – an experiment that ultimately turns out successful. Cobb is inventive, intelligent, and resourceful but also shows a recklessness in his experiments that forces him to leave loved ones behind – just like Theseus first leaves his family and later Ariadne behind on the beach of Naxos.

In fact, Cobb not only leaves his children behind, he also “binds” the memory of his dead wife Mal to certain places in his subconscious, hereunder a beach,[43] the result being that both Ariadne in the myth and Mal in Inception are left angry and frustrated. The title of the film and its meaning therefore relate to Cobb as well as Theseus, hereunder their personalities and their mission. Their situations additionally appear similar, and both narratives are set in a part real part imaginative world or time separated from our own.

Furthermore, Theseus and Cobb face the challenge of overcoming a monster in their own respect. Theseus challenges and conquers the Minotaur in the empirical world and mentally manages to overcome the sorrow and guilt connected to the abandonment of Ariadne, and his part in the suicide of his father as well as the death of his son – both lost by mistake. It is worth noting that the loss of his son is caused mostly by a mistake of Phaedra who is struck by an unnatural desire wherefore she subsequently kills herself.

Cobb challenges and defeats the external forces trying to imprison him, and shows he alone manages to handle the difficult task of making inception work. As Mal is dead, the internal memory of her and his part in her suicide haunt him, just as he is haunted by the temporary loss of his children – both also lost, yet not dead, by mistake or misunderstanding. The loss of his children is, like Phaedra’s role in the death of Hippolytos, mostly due to a mistake made by Mal, who overcome with an unnatural conception of reality, commits suicide to free herself of what she believes is a dream.[44] This illustrates how monsters exist as much in the empirical world as within our minds, and that our worst enemy is most likely to be ourselves.

As mentioned earlier in this paragraph the most direct reference between the myths surrounding Theseus and Inception is the character Ariadne, who in both storylines master the labyrinths within. Labyrinths have fascinated us throughout time, and consequently they can be found all over the world in various forms and expressions. The dictionary states that the word λαβύρινθος (labyrinthos) either refers to a building containing intricate passages, or that the word is used as a metaphor for meandering questions or arguments.[45]

Therefore, the word is connected as much to a physical structure as to a structure of the mind which makes sense in relation to the labyrinths created by Ariadne in Inception, as well as the intricate and clever plan conceived in the mind of Cobb.[46] Again, we see a play on concepts or structures of the physical world, the world of phenomena, and their reflections or alternate forms in our minds, the world of ideas.[47]

In Inception we see how Ariadne quickly forms a close relationship with Cobb thereby gaining access to his innermost thoughts, feelings, and secrets[48] – a relationship that mirrors that of Theseus and Ariadne. In Inception Ariadne functions as Cobb’s helper just like Ariadne functions as the helper of Theseus. But neither of these relationships turn out to be more than a fleeting acquaintance as both Theseus and Cobb act for the sake of a higher purpose; namely returning home. Thereby we see the importance of surrounding yourself with good friends and kind helpers, but also the negative consequence of what happens when that trust and kindness is not returned.

Of course, the negative repercussions are most closely connected to the myth of Theseus and Ariadne, as we are not informed of the further fate of Ariadne in the film. But, starting out a young and talented student of architecture, she goes on to commit a serious crime in aiding a man suspected of murder undermine the free competition in the Japanese marked, which could earn her a long prison sentence if caught. On the positive side we see how the love of one’s family and homeland are put above all else, and that hard work and determination will see you to the fulfilments of your goals in time.

Inception additionally refers to a place called Limbo;[49] the place or state of mind dreamers may end up in if they enter the world of dreams to deeply – in this sense not being conscious of or present in the empirical world, yet not having moved on to the afterlife. Although not directly connected to the myth of Theseus, one could argue that Theseus in some way enters the underworld in his pursuit of the Minotaur – a dark and mystic place disconnected from the real world; the world of the living.

Yet, according to another myth Theseus did travel to the underworld trying to aid his friend Pirithous in rescuing Persephone. Their plan did not work, and Theseus had to abandon Pirithous in Hades,[50] just like Cobb abandons Mal in Limbo. Limbo is not mentioned by that exact term in Greek mythology, but in the Odyssey there may be a connection to the Fields of Asphodel; a section of Hades where “… the souls live as dead people’s shadows.”[51] Subsequently we are told that the souls of Achilleus, Patroclos, Ajas, and Agamemnon among others dwell here.[52] This means the souls have neither entered Tartaros where the worst offenders went, nor Elysion where those selected few chosen by the gods went.[53]

Moving forward in time, the term Limbo is used by the writer Dante in his Divine Comedy (1321)[54] in his description of the first circle of Hell. Here reside the souls of people from classical mythology and history who did not sin but lived before the introduction of Christianity – hereunder Homer, Ovid, Hector, Aeneas, Caesar, Socrates and Plato.[55] In other words those lacking faith in Christianity. Therefore, Dante manages to write himself in to a classical tradition both emulating Homer among other ancient writers and honouring prominent people of the past at the same time as elevating the belief in Christianity.

The Encyclopædia Britannica holds the following information about Limbo: “In Roman Catholic theology, the border place between heaven and hell where dwell those souls who, though not condemned to punishment, are deprived of the joy of eternal existence with God in heaven.”[56] The entry further states that: “Two distinct kinds of limbo have been supposed to exist: (1) the limbus patrum (Latin: “fathers’ limbo”), which is the place where the Old Testament saints were thought to be confined until they were liberated by Christ in his “descent into hell”, and (2) the limbus infantum, or limbus puerorum (“children’s limbo), which is the abode of those who have died without actual sin but whose original sin has not been washed away by baptism.”[57]

The saints of the Old Testament represent both people and angels, consequently referring to historical and mythological figures alike. And the children inhabiting Limbo live there because they did not have the opportunity of devoting themselves to Christianity. Both these statements appear similar to how Dante described Limbo and its inhabitants in his Divine Comedy. This means that the souls of Greek mythology in the description by Homer, those mentioned by Dante in the newer Christian context, and the encyclopaedia entry thusly look alike.

Limbo is a place for those stuck between light and darkness, heaven and hell, enlightenment and ignorance, and just like the examples given above, so the people in Inception who enter Limbo remain caught between two realms; consciousness versus the subconscious. Qua Cobb’s projections of Mal he clings on to the places they created while in Limbo in this way fixating his consciousness between the land of the living and the land of the dead.[58] Furthermore, this means that Mal is confined to an existence in Limbo due to her lack of faith in Cobb and she too is caught between the land of the dead and the land of the living.

Finally, there could be a connection in how our protagonists distinguish between successes and failures or truth and lies. In the myth of Theseus, we heard how he was supposed to fly white sails as an indication to his father of everything being okay. In Inception our protagonists each always carry a so-called totem around with them – a small item whose weight and appearance are only fully known by the holder. For Cobb, this totem is a spinning top which spins indefinitely while in a dream but eventually falls over in reality.[59]

The meaning and the importance of the totem is to help Cobb and the others define whether they are in a dream or in the real world as it is not only possible but also probable to get lost in a dream.[60] The same might be said about Theseus – having conquered the Minotaur he rides a wave of triumph pulling his consciousness away from the real world and the tasks ahead. Therefore, he is lost in a dreamworld cut off from a reality where his father was counting on him and their agreement – a mistake that costs Theseus’ father his life.

While the myth ends tragically, the ending of Inception gives us no definite answer in that regard. Cobb succeeds in the task given and thusly he is allowed to return home. Before running to see his children, he spins the spinning top one last time, but he does not wait to see whether if falls over or keeps spinning.[61] By doing this, Cobb blurs the lines between dream and reality, and simultaneously tells us that he does not care, as long as he is with his loved ones.[62]

The corresponding elements underlined above draw on a variety of sources, but the connection to the myths involving Theseus appear to be prominent. The stories even share a common morale; make sure to be present in the here and now, do not lose yourself in a non-existing dreamworld, keep your promises, and have faith in those closest to you.

How does the new work place itself in the present time and why is it relevant?

Ground-breaking technology like the medicaments used in Inception to make the experiment of entering other people’s dreams work is, still, considered fiction. Yet, we live in a time where the fields of technology and science are developing at an incredible speed.

In fact, around the time Inception premiered we saw other films deal with our sense of reality and the use and misuse of technology; for example Avatar (2009) where technology is used in a destructive way. In a distant future, humans have reached the world Pandora, home of the Na’vi – the indigenous population who live above unobtanium deposits much desired by humans. In order to make the Na’vi move, genetically-bred human-Na’vi hybrids have been constructed to make the humans function as Na’vi natives.

On the surface, the goal is to learn about the customs and traditions of the Na’vi, while the higher purpose remains control of unobtanium for economic gains – just like the mission in Inception revolves around securing an economic upper hand for Saito. The focus on using technology for economic gains in Inception is stressed by Danyluk: “the stakes in the film’s heady, phantasmagorical journey into the nether reaches of the human mind boil down to a simple commercial transaction. Such are the symptomatic silences that haunt contemporary mass culture: of all the applications one could imagine for a device that lets people enter each other’s dreams, Hollywood can think of none more inspired than facilitating a corporate takeover.”[64]

According to this, both films remain flat and unimaginative, when they had the opportunity of being so much more. Consider how both films would have been received had they focused more on developing and enhancing our brainpower and the consequences of such a feat.[65]

Technology also plays a large part in Iron Man 2 (2010) – again used in connection to wealth and power. Billionaire Tony Stark, now known to the world as Iron Man, is seeking to change his course from supplying militant groups with weapons to channeling his knowledge and resources into more peacekeeping activities. Still, various organizations, nations, and criminals wish to get their hands on the powerful technology invented by Stark, who himself is under pressure to invent a better alternative to the artificial “heart” – a so-called “arc reactor” – that prevents shrapnel from piercing his real heart. Stark then faces his own interests contrasting the interests of the USA and others.

The film seems to contemplate whether it is possible to use the massively destructive weapons of Stark industries for a higher purpose or if the use of weaponry in conflicts is always a bad thing. This consideration appears highly relevant as the past decades in the Western world have revolved around fighting those opposed to traditional Western values, beliefs, and forms of governance.

Not only the dangers and possibilities of technology constituted the themes of various movies around this time. A focus on identity and consciousness also played a large part, for example in the films Alice in Wonderland (2010) and Shutter Island (2010), where the protagonists both see themselves entering another world. Alice in Wonderland is a retelling of the children’s book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865).[66] In the film Alice, now nineteen years old, reenters Wonderland – the place she equals not with reality, but with nightmares from her childhood.

In Wonderland she encounters strange beings, talking animals, and an evil queen whose reign Alice needs to end. While we could believe that Alice simply returned to an old nightmare trying to escape her own engagement party, the beings and animals of Wonderland are seen in the real world on several occasions. In this way separating dream, an alternate world, and reality is deemed difficult and even impossible, as all in the end are intertwined.

The same might be said of Shutter Island which just like Inception features Leonardo DiCaprio as the film’s main protagonist. The plot revolves around the U.S. Marshall Teddy Daniels (DiCaprio) who is assigned the investigation of a missing patient from a hospital on Shutter Island which houses a mental asylum for dangerous patients and criminals. Daniels soon makes progress but the doctors on the island deny him access to certain records thereby complicating the case.

When communication to the mainland is cut by the arrival of a hurricane, more patients escape all the while Daniels’ migraine-like flashbacks of WWII and his wife’s death in a fire increase. Due to strange encounters on the island, Daniels soon begins to question the doctors, his partner, and even himself. Who can be trusted, and can Daniels trust his own sanity? The film plays on good versus evil, truth versus lie, and consciousness versus the subconscious – much like Inception.

Of course, many other films premiered around this time, but these examples convey the impression that the themes technology versus money and people’s perception not only of themselves and their identity but also of reality form a pattern that might be able to tell us something about the time in which these films aired. In a world where we are able to travel both physically and mentally around the globe in a short amount of time, and in a world where the Internet governs our choices and allow us to appear as someone or something that we are not – then how are we to navigate the world in general and our own lives specifically?

It appears as if it is becoming increasingly difficult to define who we are both in terms of gender, sexuality, nationality and more. The monster in our current labyrinth of life thus becomes ourselves, our impression of the world around us, and our use of technology. Because, in a world increasingly dominated by virtual reality it seems to be ever more arduous to distinguish between what is real and what is not.[67] An increased focus on time, history, and (collective) memory then seems to be of the essence – lest we forget who we were and thereby who we are, and eventually who we are going to become.

Has the use of the original source had an impact on the audience or short or long-term effects elsewhere?

Apparently, the connections between the myths surrounding Theseus and his deeds and the film Inception do not strike one as being neither obvious, that is for an audience not acquainted with myths from classical Greece, nor having been disseminated from Inception specifically to other modern works. The mentions of the similarities are scarce, and researchers tend to focus on other elements of the film than the classical references. Yet, the film in general and the characters within underline the importance of dreaming up new things and being original,[68] which might be deemed ironic taking its borrowings from the ancient world into consideration. Nonetheless, this may be one of the film’s most important lessons; in a time governed by reboots and prequels,[69] we need creativity and innovation more than ever.

Conclusion

The film Inception and the myths surrounding the ancient hero Theseus are quite different, yet they share several important elements, which leads us to think that the references were applied to the new context deliberately. This is supported by the educational background of writer and director Christopher Nolan, who studied English literature at University College London prior to his filmmaking career.

The works and writers mentioned in the curriculum relate to works and writers from classical antiquity, therefore indicating that Nolan gained some sort of knowledge of this period through his studies. Furthermore, Nolan’s use of the unusual name Ariadne and the concept of Catharsis clearly point to a knowledge of several aspects of myths and writings of the ancient world, which underlines the intentional application of the same in the new context.

While the form differs between the two works, the characters of Cobb/Theseus, Mal/Phaedra, and Ariadne/Ariadne have much in common in relation to their personalities, actions, and roles. The same goes for their rational objectives which in both cases contrast their more subconscious desires – a conflict that often ends in despair.

The most obvious parallel between the use of myths from classical antiquity and Inception remains the name Ariadne – a name that might ring a bell with at least part of the audience. Being so closely connected to the myth of Theseus and him overcoming the Minotaur, Ariadne’s name may lead the part of the audience in the know to consider other similarities between the myth and the film, while others might stay oblivious to the reference. Yet, by naming a creator of labyrinth dreamscapes Ariadne, Nolan clearly underlines the correspondences between myth and film. He does this in order to show us the consequences of our actions, how our behavior affects other people – especially those closest to us, and how we can be blinded by dreams, desires and deceptions.

The conscious as opposed to the subconscious and the dangers of living in a dreamworld is underlined in both works. This relates somewhat to our modern world, its wheels ever in motion, making it problematic as well as exhausting to keep up. New technology aids us in our daily lives, but also adds pressure on our minds – forcing us to keep up with the newest developments, inventions, or labels with which we define each other. The world keeps getting smaller through the use of technology, but the easy access to insurmountable amounts of information broadens our choices and possibly makes us lose focus of tasks ahead.

In the end the question thusly remains: in a world where you can be anything – what do you choose to be?

Footnotes

[1] Aristotle, On Dreams, §3

[2] See for example Louise Jensby “Harry Potter and the Greek treasure trove – How and why Greek myths were incorporated into a modern magical epic” in http://fantastischeantike.de/harry-potter-and-the-greek-treasure-trove-how-and-why-greek-myths-were-incorporated-into-a-modern-magical-epic/

[3] Olson, 47, 50

[4][4] Lisa K. Perdigao, “’The dream has become their reality’: Infinite Regression in Christopher Nolan’s Memento and Inception”, 125

[5] Sorcha Ní Fhlainn “’You keep telling yourself what you know, but what do you believe?’: Cultural Spin, Puzzle Films and Mind Games in the Cinema of Christopher Nolan”, 156

[6] Jacqueline Furby “About Time Too: From Interstellar to Following, Christopher Nolan’s Continuing Preoccupation With Time-Travel”, 255

[7] Todd McGowan, The Fictional Christopher Nolan, 157

[8] David Kyle Johnson, “Inception and Philosophy: Life Is But a Dream” in https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/plato-pop/201111/inception-and-philosophy-life-is-dream

[9] Christian Gorm Tortzen, Antik mytologi, 333

[10] Arthur Cotterell & Rachel Storm, The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology, 50, 64, 76-77, 84-85

[11] Ibid., 64

[12] Tortzen, 333-334

[13] Cotterell & Storm, 75. See also Euripides, Hippolytos, 724-1102. In the end Hippolytos dies as well after Poseidon sends a bull-like beast to kill him, Euripides, 1213-1248

[14] Cotterell & Storm, 25, 64

[15] Den Store Danske, “Ovid” in Den Store Danske

[16] Ovid, Metamorphoses XV 497-529 and VIII 152-168

[17] Christian Gorm Tortzen, “Faidra” in Den Store Danske

[18] Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives, Theseus. For the two latter myths, Ariadne, the labyrinth and the Minotaur, and the myth about Hippolytos see 15.1-20.5 and 28.1-28.2 respectively

[19] Bodil Due, ”Plutarch” in Den Store Danske. See also “Parallel lives” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parallel-Lives

[20] Marianne Børch, “Geoffrey Chaucer” in Den Store Danske

[21] Thomas Pettitt, “William Shakespeare” in Den Store Danske

[22] Shakespeare, The Two Noble Kinsmen, frontmatter

[23] For more on Theseus’ role in these plays and his reputation both in classical antiquity and in the Renaissance see D’Orsay W. Pearson “”Unkinde” Theseus: A Study in Renaissance Mythography”

[24] ”Phèdre” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Phedre

[25] Chaucer 1400, 3

[26] For a closer study on how to categorize books, films, or other kinds of material reusing parts of classical antiquity see Lorna Hardwick Reception Studies, 9-10

[27] Steven Zeitchik, “Which dystopian property does ‘The Hunger Games’ most resemble?” in https://web.archive.org/web/20120327161259/http://www.bostonherald.com/entertainment/movies/general/view/20120324which_dystopian_property_does_the_hunger_games_most_resemble

[28] For the scene with the Minotaur – a man wearing a bull-mask see Immortals, 46.53-50.50

[29] For other examples see Frances Babbage “Leaving the Labyrinth: Hella S. Haase’s A Thread in the Dark (De Draad in het Donker)”

[30] IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0634240/bio?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm

[31] UCL: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/prospective-students/undergraduate/degrees/english-ba/2020

[32] Ibid.

[33] Shakespeare repeatedly found inspiration in Greek and Roman myth and history which can be seen by the plays Julius Caesar, Troilus and Cressida, and Anthony and Cleopatra

[34]UCL: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/prospective-students/undergraduate/degrees/english-ba/2020

[35] Børch, “Geoffrey Chaucer” in Den Store Danske. Ovid tells the tale of the Minotaur and Ariadne in his Metamorphoses, VIII 152-182

[36] Inception, 50.43 and 1.23.14. See also Darren Mooney, Christopher Nolan: A Critical Study of the Films, 93

[37] Aristoteles, Poetikken, 65, or ”Catharsis” in Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/art/catharsis-criticism. For a reference to the Greek word see LSJ: “κάθαρσις” (katharsis): “A. cleansing from guilt or defilement, purification”

[38] David Heuring, “Dream thieves” in https://theasc.com/ac_magazine/July2010/Inception/page1.html. See also Mooney 2018, 96

[39] See McGowan, 7-18 for a view on deception in films and how Nolan emphasizes the importance of deception. See also Mooney 2018, 88 on the similarities between dreams, movies, filmmaking, changing locations, and distortions of time

[40] The same can be stated in connection to ancient plays which often did not feature the most horrible scenes. Instead, these were unfolded by messengers who elaborately described the often macabre deaths of the protagonists. This is seen for example in Euripides, 1173-1254 or Sofokles’ Kong Ødipus, 1237-1285

[41] ”Inception” in https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/inception

[42] ”Inception” in https://www.etymonline.com/word/inception

[43] Inception, 56.00-56.24

[44] Ibid., 1.58.56-1.21.10

[45] LSJ: “λαβύρινθος” (labyrinthos): “A. labyrinth or maze, a large building consisting of numerous halls connected by intricate and tortuous passages” or: “2. prov. of tortuous questions or arguments”. See also etymonline: https://www.etymonline.com/word/labyrinth. In The Idea of the Labyrinth: from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Dobb too addresses the etymology of the words labyrinth and maze, including an interpretation meaning “hardship lies inside”, 95-99

[46] Jerzy Kociatkiewicz and Monika Kostera also address labyrinths as both linguistic, metaphorical, and spatial constructions in “Into the Labyrinth: Tales of Organizational Nomadism”. The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur is even mentioned on several occasions. Reed Dobb 1990, mentions how Pliny dealt with the facts of ancient labyrinths, how Ovid concentrated on the myths surrounding them, and how Virgil was fascinated by both the labyrinths’ structure and the stories connected to them, 17-38

[47] For more on the connection between the two concepts see Anne-Marie Eggert Olsen ”Platon” in Den Store Danske, see also Platon Staten, 15-17, and Louise Jensby Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” Reimagined – The Maze Runner as a Modern Interpretation” in http://fantastischeantike.de/platos-allegory-of-the-cave-reimagined-the-maze-runner-as-a-modern-interpretation/

[48] Inception, 24.44-34.36, 54.38-1.01.21, 1.15.28-1.22.15

[49] Ibid, 1.08.37-1.09.21

[50] ”Theseus” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Theseus-Greek-hero

[51] Homer, Odysseen XXIIII, 14. My translation

[52] Ibid. 15-20

[53] Tortzen, 331 and 283

[54] Jørn Moestrup, ”Den guddommelige komedie” in Den Store Danske

[55] Dante, Den Guddommelige Komedie, Helvedet IV, 31-45 and 88-133

[56] ”Limbo” in Encyclopædia Britannicae https://www.britannica.com/topic/limbo-Roman-Catholic-theology

[57] Ibid.

[58] See for example Perdigao 2015, 124 and Furby 2015, 256

[59] Inception, 15.48, 33.40-34.22, 44.14-44.25, and 48.29-48.51. Yet, several researchers have commented on the problematic in Cobb using the spinning top as his totem and thereby his connection to reality, as it originally belonged to Mal

[60] See also Fran Pheasant-Kelly, “Representing Trauma: Grief, Amnesia and Traumatic Memory in Nolan’s New Millennial Films” for thoughts on how trauma affects the memory. The article addresses this issue in connection to Nolan’s films, but parallels can be drawn to Theseus and his traumatic experiences with the Minotaur and his following actions and memory loss which causes the death of his father

[61] Inception, 2.20.03-2.20.53

[62] For more on Cobbs difficulty of distinguishing between dream and reality see Perdigao, 2015

[63] Photo by Louise Jensby

[64] Martin Danyluk, “Dreaming Other Worlds: Commodity Culture, Mass Desire, and the Ideology of Inception”, 607

[65] For a film that investigates precisely this issue see Lucy, a film that premiered in 2014

[66] Tove Thage, Viggo Hjørnager Pedersen: ”Lewis Carroll” in Den Store Danske

[67] See also McGowan, 147

[68] See also Mooney 2018, 87

[69] Ibid., 86-87

Bibliography

Books

Aristotle. 2015. On Dreams. Translated by J. I. Beare. The University of Adelaide, eBooks@Adelaide

Aristoteles. 2004. Poetikken. Translated by Niels Henningsen. DET lille FORLAG, Copenhagen

Carroll, Lewis. 1865. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. 1400. The Knight’s Tale. TaleBooks.com

Collins, Suzanne. 2008. The Hunger Games. Scholastic

Collins, Suzanne. 2009. Catching Fire. Scholastic

Collins, Suzanne. 2010. Mockingjay. Scholastic

Cotterell, Arthur, Storm, Rachel. 2015. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology. Anness Publishing Ltd

Dante. 2000. Dantes Guddommelige Komedie. Translated by Ole Meyer, Multivers

Euripides. 1951. Hippolytos. Translated by P. Østbye. Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag

Furby, Jacqueline, Joy, Stuart. 2015. the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Edited by Jacqueline Furby and Stuart Joy. Columbia University Press

Hardwick, Lorna. 2003. Reception Studies. Oxford University Press

Homer. 2002. Odysseen. Translated by Otto Steen Due. 2. edition, Gyldendal

Liddell, Henry George, Scott, Robert & Jones, Sir Henry Stuart. (LSJ) 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon. Clarendon Press, Oxford

McGowan, Todd. 2012. The Fictional Christopher Nolan. The University of Texas Press

Mooney, Darren. 2018. Christopher Nolan: A Critical Study of the Films. McFarland & Company Inc.

Ovid. 2005. Ovids Metamorfoser. Translated by Otto Steen Due. 2. Edition, Gyldendal

Platon. 1999. Staten. Translated by Otto Foss. Museum Tusculanums Forlag, Copenhagen

Plutarch. 1994. Plutarch’s Lives, Theseus. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. William Heinemann Ltd Harvard University Press, London

Reed Dobb, Penelope. 1990. The Idea of the Labyrinth: from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press

Robinson, Tony, Curtis, Richard. 1988. Theseus: The King Who Killed the Minotaur. Hodder & Stoughton

Seneca. 2008. Phaedra. Translated by Simon Laursen in http://klassisk.ribekatedralskole.dk/personer/seneca/Phaedratotal.pdf

Shakespeare, William. 1998. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The EMC Masterpiece Series Access Editions, Series Editor Robert D. Shepherd. EMC/Paradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota

Shakespeare. 2015. Anthony and Cleopatra. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. Folger Shakespeare Library https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/download/

Shakespeare. 2015. Julius Caesar. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. Folger Shakespeare Library https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/download/

Shakespeare. 2015. Troilus and Cressida. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. Folger Shakespeare Library https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/download/

Shakespeare. 2018. The Two Noble Kinsmen. Global Grey

Sofokles. 1977. Kong Ødipus. Translated by Otto Foss. 2. Edition, Otto Foss and Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen

Tortzen, Christian Gorm. 2009. Antik Mytologi. Third edition, Chr. Gorm Tortzen and Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen

Articles

Babbage, Frances. 2000. “Leaving the Labyrinth: Hella S. Haase’s A Thread in the Dark (De Draad in het Donker)” in Modern Drama, Vol. 43, Nr. 1

Børch, Marianne. 2017. Article about “Geoffrey Chaucer” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Danyluk, Martin. 2015. “Dreaming Other Worlds: Commodity Culture, Mass Desire, and the Ideology of Inception” in Rethinking Marxism, 27:4, 601-610

Den Store Danske. 2017. Article about “Ovid” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Due, Bodil. 2017. Article about ”Plutarch” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Eggert Olsen, Anne-Marie. 2017. Article about ”Platon” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Encyclopædia Britannica. Article about ”Limbo” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/limbo-Roman-Catholic-theology

Encyclopædia Britannica. Article about “Parallel lives” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parallel-Lives

Encyclopædia Britannica. Article about ”Phèdre” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Phedre

Encyclopædia Britannica. Article about “Theseus” in Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Theseus-Greek-hero

Fhlainn, Sorcha Ní. 2015 “’You keep telling yourself what you know, but what do you believe?’: Cultural Spin, Puzzle Films and Mind Games in the Cinema of Christopher Nolan” in the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Columbia University Press

Furby, Jacqueline. 2015. “About Time Too: From Interstellar to Following, Christopher Nolan’s Continuing Preoccupation With Time-Travel” in the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Columbia University Press

Heuring, David. 2010. “Dream thieves” in https://theasc.com/ac_magazine/July2010/Inception/page1.html

Jensby, Louise. 2018. “Harry Potter and the Greek treasure trove – How and why Greek myths were incorporated into a modern magical epic” in http://fantastischeantike.de/harry-potter-and-the-greek-treasure-trove-how-and-why-greek-myths-were-incorporated-into-a-modern-magical-epic/

Jensby, Louise. 2019. “Allegory of the Cave” Reimagined – The Maze Runner as a Modern Interpretation” in http://fantastischeantike.de/platos-allegory-of-the-cave-reimagined-the-maze-runner-as-a-modern-interpretation/

Johnson, David Kyle. 2011. “Inception and Philosophy: Life Is But a Dream” in https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/plato-pop/201111/inception-and-philosophy-life-is-dream

Kociatkiewicz, Jerzy, Kostera, Monika. 2015. “Into the Labyrinth: Tales of Organizational Nomadism” in Organization Studies, Vol. 36

Moestrup, Jørn. 2017. Article about ”Den guddommelige komedie” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Olson, Jonathan R. 2015. “Nolan’s Immersive Allegories of Filmmaking in Inception and The Prestige” in the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Columbia University Press

Pearson, D’Orsay W. 1974. “”Unkinde” Theseus: A Study in Renaissance Mythography” in English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 4, No. 2. The University of Chicago Press

Perdigao, Lisa K. 2015 “’The dream has become their reality’: Infinite Regression in Christopher Nolan’s Memento and Inception” in the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Columbia University Press

Pettitt Thomas. 2017. Article about “William Shakespeare” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Pheasant-Kelly, Fran. 2015. “Representing Trauma: Grief, Amnesia and Traumatic Memory in Nolan’s New Millennial Films” in the cinema of Christopher Nolan imagining the impossible. Columbia University Press

Thage, Tove, Hjørnager Pedersen, Viggo. 2017. Article about ”Lewis Carroll” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Tortzen, Christian Gorm. 2017. Article about “Faidra” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Zeitchik, Steven. 2012. “Which dystopian property does ‘The Hunger Games’ most resemble?” in Los Angeles Times https://web.archive.org/web/20120327161259/http://www.bostonherald.com/entertainment/movies/general/view/20120324which_dystopian_property_does_the_hunger_games_most_resemble

Films

Alice in Wonderland. 2010. Walt Disney Pictures, Roth Films, Team Todd, The Zanuck Company, Tim Burton Productions

Avatar. 2009. Twentieth Century Fox, Dune Entertainment, Lightstorm Entertainment

Immortals. 2011. Relativity Media, Virgin Produced, Mark Canton Productions, Atmosphere Entertainment MM, Hollywood Gang Productions, Mel’s Cite du Cinema

Inception. 2010. Warner Bros., Legendary Entertainment, Syncopy

Iron Man 2. 2010. Paramount Pictures, Marvel Entertainment, Marvel Studios, Fairview Entertainment

Lucy. 2014. EuropaCorp, TF1 Films Production, Grive Productions, Canal+, Ciné+, TF1, Filmagic Pictures Co., Element Film, Centre National du Cinéma et de L’image Animée

Shutter Island. 2010. Paramount Pictures, Phoenix Pictures, Sikelia Productions, Appian Way, John Thomas Special FX

2001: A Space Odyssey. 1968. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Stanley Kubrick Productions

Links

Cambridge English Dictionary: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/

Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/

Folger Digital Texts: https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/download/

Online Etymology Dictionary: https://www.etymonline.com/

IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/

The American Society of Cinematographers: https://theasc.com/

University College London: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/