Veröffentlicht: 17. Dezember 2018 – Letzte Aktualisierung: 20. September 2022

Introduction

In ancient Greek the word μῦθος (mythos) simply means word, speech or story, but can also carry the connotations normally associated with the word “myth” today: namely fiction, legend or fable.[1] In recent years books and films alike have provided us with a cornucopia of fantastical tales of gods, heroes and mystical creatures. The genre of fantasy seems to be getting ever more popular, and looking to the future, it appears we still have a lot to look forward to from companies such as Marvel, DC Comics and the Harry Potter universe. The films from these and other companies tend to mix ancient myths with later and more modern narratives and events, leaving us wondering how and more importantly why the writers in question have chosen to let these different myths and time periods unite.

The study of how the past is being used in various contexts is fairly new, and this specifically applies to the study of history on film. This particular field of research has suffered under the impression of not being historically interesting nor having a scientific potential, but during the last 20 years or so the attitude among researchers has changed. For instance, this tendency is seen via the incorporation of new methodological history courses at universities and via the development of new fields of research and analysis strategies. Yet the problem still is that even though new ways of dealing with the use and reception of history have appeared, almost none of these analysis strategies focus on how to analyse and understand the use of history on film in a scientific way. Therefore, this article introduces two fields of research and focuses on finding a way of combining elements from both in order to apply the result on a specific film. The fields uses of history and reception studies both provide us with useful tools when conducting various analysis in books or elsewhere, which is why I among others, recognize the fields’ methodological approaches as useful when it comes to analysing films as well. The results of this experiment in merging two theories will be applied to the first Harry Potter movie; Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Released 2001, hereafter HPPS) – the first instalment in a series of eight films based on seven books. But first, an introduction to the Harry Potter universe seems to be in order.

The Harry Potter experience

It should not come as a surprise that the books and movies featuring Harry Potter take place in England in a world where both magical and non-magical beings exist. The magical world is fighting to remain hidden from all Muggles – non-magical humans – at the same time as an old enemy is surfacing again threatening all “half-blood”-magicians, “half-breed” creatures and the secrecy surrounding the magical world. Harry Potter remains oblivious of all of this until his 11th birthday, where he is contacted by Albus Dumbledore – the headmaster of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Because of the untimely death of Harry’s parents, he is at the time living with his aunt and uncle, who have installed him in a cupboard under the stairs. This, among other things, fuels Harry’s adventurous spirit, and he does not need much incitement to give up his current life in exchange for a spot on Hogwarts – an event that changes Harry’s life in every way imaginable.

This fantastical tale of a lonely boy turned successful wizard originated in the mind of British writer Joanne Rowling in 1990 whilst sitting on a train. During the following five years she planned the course of events[2] in what would become seven of the most successful books written to this date. Since the first book was published in 1997 the franchise has spawned eight Harry Potter movies, a play called Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (2016), two prequels in which we follow in the footsteps of magizoologist Newt Scamander, an amusement park, merchandize and much more. Yet in this British semi-real, semi-magical universe traces of ancient Greek mythology can be identified, which is why an attempt of listing and analysing these possibly misplaced, possibly intentionally constructed scenes and traces will be carried out in the following. This necessitates a theoretical basis which will be introduced in the next section.

The theory of uncovering history on film[3]

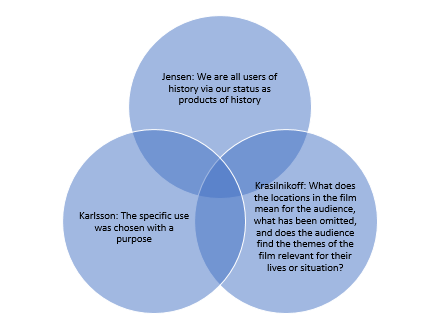

Mixing the past and the present might not be a new or ground-breaking idea – but the study of which periods have been combined to form something new, and more importantly why, is attracting ever more attention. The fields uses of history and receptions studies have proven effective in providing us with new methods in which to analyse and look at how the past is being used and perceived in various situations. Even though the two fields overlap in places, they basically focus on different approaches in dealing with the application of the past in new contexts. Where uses of history focuses on how and why people use the past in different ways, what it means when specific parts of the source material is added or left out, and what the new work says about its present time, reception studies focuses on how the new source is related to the old, and what implications the journey the original source has undertaken to the new context or format have had for the end-result. Researchers around the world have suggested alternate ways of examining the issue presented in this article, and what follows offers an overview of some of the thoughts on the subject of a handful researchers.

The past can be used consciously or subconsciously, which might have something to do with what can be derived from this quote by Danish historian Bernard Eric Jensen: “History is understood as those processes people help generate through their actions, and people are considered both products of history as well as producers of history.”[4] This points to the perception that all individuals approach a given situation or a given work with a set of expectations, which is going to have an effect on the new set of references, no matter if you are the passive recipient of a work or the active creator of one. A person’s remembrance of history is thereby constituted of that person’s interpretation of the past, understanding of the present and expectations of the future.[5] A close coherence exists between these three temporal understandings of the world, and though the quote and the concepts above might seem a bit airy, the key is that because we are indeed all products of history, our interpretation of the past will always be a part of our understanding of the present and our expectations of the future.

The Swedish historian Klas-Göran Karlsson is more specific when it comes to labelling the distinct uses of the past, as he has come up with the following way of categorizing any use of history:

- A scientific use: refers to the interpretive but methodological way history is being used by teachers and researchers

- An existential use: gives groups or individuals the opportunity of drawing on certain memories or events to create a shared identity or frame of reference

- A moral use: used to rehabilitate or emphasize forgotten or neglected groups or events

- A political use: history is used comparatively or metaphorically to legitimize political opinions or decisions

- An ideological use: also has a legitimizing purpose, yet on an overall scale used in the claim of tracts of land or similar

- A non-use: a deliberate omission or effacing use of history in an attempt of forgetting certain events or to distance yourself from them

- A commercial use: history is used in films or commercials to promote a certain product[6]

Obviously the chosen film falls under the category of commercial use,[7] but in my opinion this observation appears somewhat hollow and needs to be supported by other findings.

Danish historian Jens A. Krasilnikoff has also expressed his view on the inadequacy of Karlsson’s typologies, and he suggests that a spatial consideration should be added to the equation.[8] The locations shown in the films contribute to the formation an individual identity among the audience qua the physical relevance of the locations as well as the things the locations represent through the historical events that have taken place at the site. For Krasilnikoff the essential part of the analysis lies in identifying what has been omitted from the original source and why, and furthermore determining which elements of the film’s plot and themes that the audience might find entertaining or to have contemporary relevance.[9]

Of these three models, the one put forth by Krasilnikoff offers us the most thorough tools in the interpretation of a given film. Yet if we accept the fact that we are all users of history, I believe it is important to examine whether the use was intentional or not – that is an analysis of the individual user’s possible knowledge of the original source – an issue not touched directly upon or extensively unfolded in the chosen texts by the three abovementioned historians.[10] For this branch of the analysis, reception studies might provide us with the tools missing in uses of history.

The German literary historian Hans Robert Jauss has stated that: “The literary work is not an isolated existing object appearing in a similar way for every viewer at any given time.”[11] The fact that I am the one interpreting HPPS in 2018 thereby has an effect on the current analysis. Consciously or subconsciously my personal and professional experience stays with me when reading or analysing something new. No matter how hard I try to stay objective when conducting an analysis, it will end up being a subjective representation of my experiences and expectations. Jauss further states that any reader/viewer approaches a work with a specific horizon of expectations, stemming from what that person has previously read or watched. If the audience’s horizon of expectations is met, the book or film is more likely to be deemed a success. If on the other hand the horizon of expectations is not met to a sufficient extent, the audience might find the book or film to be a flop.[12] It therefore becomes important to look at what the work means to whom, and what might have changed over time. This is reflected in Jauss’ model: writer-work-audience, in this case J.K. Rowling-HPPS-audience, where the active part of the audience is underlined. This triangle is then transformed into what Jauss calls The Dialogical Relationship expressed in the model: work-audience-new work, where the audience becomes producers of history via the dissemination of their own experiences in a new work. The point being that their opinions or interpretations then might have an influence on the next line of readers/viewers, relating to the new work instead of the original.

The relationship between these works is addressed by professor and classicist Lorna Hardwick, who describes reception studies as the double-sided relationship between the original text/culture and the new work/reception culture. She focuses on three aspects of the analysis:

- How was the text received or transformed by the artist, and how does the new work relate to the original text?

- What does the recipient know of the original text, and how did they achieve this knowledge?

- What is the purpose of the use of the original text in the new context?[13]

Some of these points overlap with the points put forth by Krasilnikoff. Hardwick’s first statement is similar to Krasilnikoff’s thoughts on how the film uses the past and which things were omitted and why. Hardwick’s third point also mirrors Krasilnikoff’s point of why the changes were made, and thereby it becomes apparent that similarities between the two fields of research exists. Something different is the extensive list of useful concepts outlined by Hardwick. I will restrain myself from mentioning them all, but I will list a few that I find particularly applicable:

- Acculturation: assimilation to a new cultural context

- Adaptation: a version of the source is developed for a different purpose than the original

- Appropriation: the source is changed with the purpose of legitimizing ideas or actions

- Correspondence: formal aspects transferred directly from the source to the new work

- Equivalent: the source and the new work fulfil a similar role, but does not necessarily resemble each other in form or content

- Foreignization: the differences between the source and the new work are highlighted

- Hybrid: material from more sources or cultures are merged in a new work

- Transplant: the source is placed in a new context where it can develop

- Version: a use of the source which is too free to count as a translation[14]

These concepts can be applied to both the form of the new work as opposed to the original, how these relate to each other and to specific scenes, which heightens the relevance of reception studies per se, and Hardwicks terms specifically.

As shown above, uses of history concerns itself with focusing on the meaning of the use of the past, and what additions or omissions mean in the present case. Reception theory is centred on the journey through time or format of the original source, how the user gained knowledge of the source and how the new work is different from or like the original. To get the most out of these different theoretical approaches, I suggest the following model:

- Who is the user, and through which channels did they gain knowledge of the source?

- Is the use intentional?

- How does the form, content/scenes – including additions or omissions – and characters of the new work relate to the source and why?

- How does the new work place itself in the present time and why is it relevant?

- Has the use of the original source had an impact on the audience or short or long-term effects elsewhere?

The first two questions are centred around the source and the creator of the new work, thereby pointing backwards in time seeking to establish the connection between the source and the user. The next two questions help us understand how the old and the new work are related and places the new work in its present time. The last question looks at the consequences of the use of the past in the new context enabling us to take look at the future.

With the abovementioned results in mind an investigation of the Greek infiltration of modern magical London will be conducted hereafter.

Harry Potter and the incorporation of Greek myth

Who is the user and is the use intentional?

As we have seen, references to the past can be made intentionally or unintentionally. But if the use of the past was not intended –where did the knowledge of the historical event or person come from? Some events from the past have ended up having such an iconic status that they have been embedded into our own history, society and mindsets resulting in us not even knowing when we are passing on myths or events from a different age. Yet it is still possible to trace a person’s likely knowledge of certain topics via their interests, educational history or similar.

As mentioned in “The Harry Potter experience”, Harry Potter and his fantastical universe was made up by J.K. Rowling – a teacher who also worked as a writer in her spare time.[15] Rowling has stated that two-thirds of the mythological universe in the Harry Potter books is her own invention, and that one-third draws on myths and legends from Britain’s own past.[16] This raises some interesting questions, for if the contents of the novels/films is based solely on Rowling’s imagination and Britain’s mythic past, then what is a human turned into a pig, a three-headed dog and a boy “in love” with his own reflection doing there? The vigilant reader might have caught my hints at Odysseus’ men and their meeting with Circe, Kerberos and finally Narcissus – all well-known ancient myths or parts of such and thereby not self-invented or part of British myth. This infiltration of the classical world with modern magical London may seem farfetched, but giving the fact that Rowling studied Classics at Exeter University,[17] the connection with and the use of ancient Greek myths may seem less caught out of the blue. Having studied Classics, Rowling must have had a wide and accurate knowledge of the adventures of Odysseus, of Kerberos guarding Hades, and mythic characters like Narcissus. That Rowling does not mention her being inspired by these classical texts and myths could be an accidental omission from her side. It could also be the case that the Greek myths subconsciously have become a part of our, and thereby Rowling’s, collective memory and therefore a shared past not explicitly questioned by anyone – a Greek treasure trove free for the taking so to speak. On the other hand, Rowling possibly felt that addressing the similarities with the Greek starting point was irrelevant, because her version differed enough from the original. The fact is, that the film is perfectly watchable without having any knowledge of a Greek mythological past, but nonetheless I among others did notice these similarities. Thereby these scenes and references come to mean different things for those in the know and those who are not. Whether or not the specific scenes differ enough from the original and thereby are not to be considered, will be addressed in the following.

Form, content and characters

HPPS is a story, and here a film, taking place in modern London – quite far from the ancient Greek starting point of orally transferred myths and legends. But when taking into consideration that rhapsodes (ῥαψῳδός sg.) would wander from polis to polis performing their songs and gathering a crowd who were left with the same collective experience afterwards, the showing of a film at a movie-theatre for a specific audience might not be a huge leap after all. Yes, the setting and technology is different, but the audience is still left with the same material as the Greeks were at any given recital and then interpreted by them according to their former experiences and expectations. A modern day audience or reader may have the advantage of being able to revisit the film or book thus experiencing and interpreting the story and characters from anew, but this does not mean that the audience or reader will necessarily change their attitude towards the work – just like the ancient Greek audience probably had certain opinions about well-known characters like Achilleus, Odysseus or Agamemnon prior to the rhapsode singing about them or the Trojan war.

The film contains various scenes that mirrors examples from classical antiquity. Let us start with the semi-metamorphosis of Dudley Dursley. Trying to avoid the letters that keep coming from Dumbledore inviting Harry to go to Hogwarts, the Dursleys dragging Harry along, take refuge in a shed on an island.[18] In the Odyssey Odysseus and his men also arrive at a seemingly deserted island, and an exploration team is sent on their way after Odysseus sees smoke coming from somewhere further inland.[19] In both stories magical encounters occur; in the Odyssey all but one from the search party are turned into swine by the sorceress Circe,[20] and in HPPS the friendly half-giant Hagrid equips Harry’s cousin Dudley with a pigtail.[21] Both Circe and Hagrid are the only ones in possession of actual magical powers at the time, whereby the other characters appear as mere bystanders. The difference is that where we consider Odysseus’ men a part of the protagonist-group unrightfully treated by Circe, we cannot help but feel that justice is done when Dudley the overly spoiled bully gets what he deserves; namely a pigtail whilst eating Harry’s birthday cake.[22] In the Odyssey – having been performed during the time when the Greeks were founding colonies all over the Mediterranean – the witch (Circe) functions as a potential and real threat and stopper for Odysseus and his men, making us aware that strangers and those who are different can be dangerous. In HPPS on the other hand, we find ourselves rooting for the witches and wizards and the world they belong to, suggesting that we are more open to, or at least more used to, interacting with cultures and beliefs that differ from our own in the 21st century – in Hardwick’s words deeming the use an adaptation.

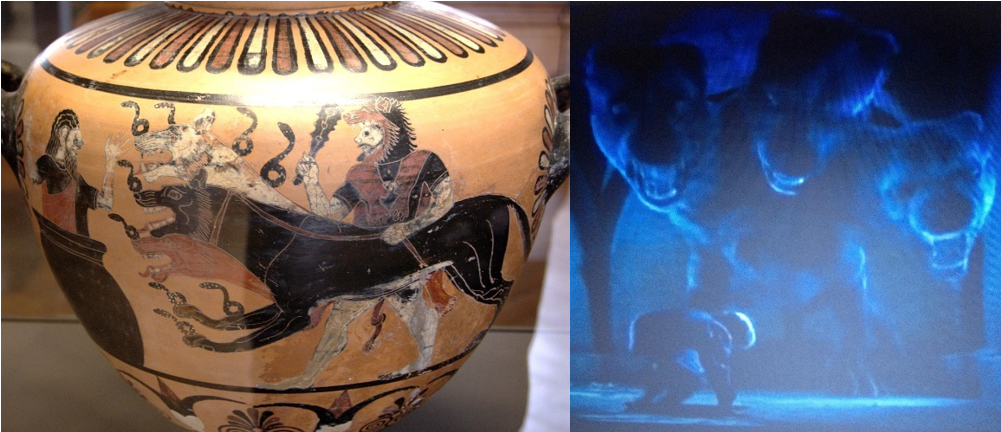

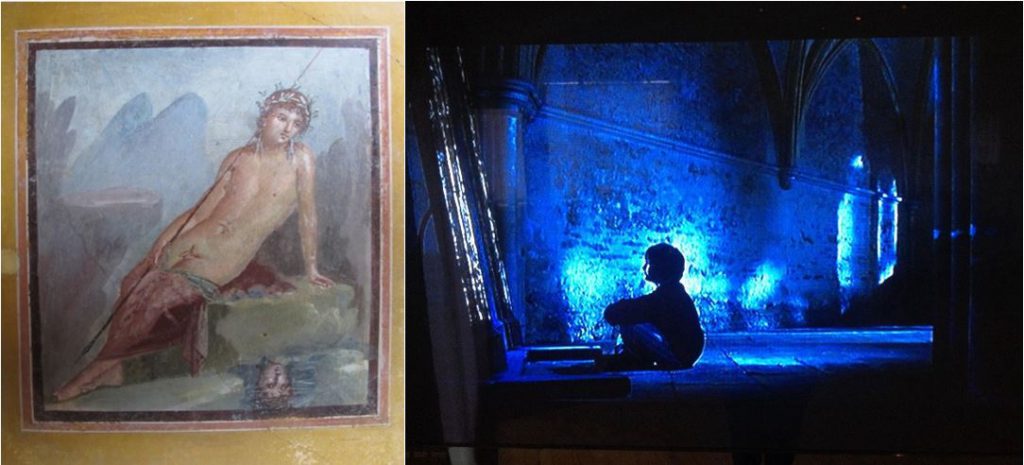

While wandering the hallways of Hogwarts our three heroes Harry, Ron and Hermione come across a three-headed dog named Fluffy – first time around by accident, second time around while searching for the Philosopher’s Stone.[23] A three-headed dog is a bit out of the ordinary – but not in Greek mythology. Here we find the dog Kerberos with three heads guarding the gates of Hades in the underworld. Like Kerberos Fluffy is also guarding something that lies beneath a hatch in the floor – that is something under the ground, making the two situations appear analogous. The difference is, that Kerberos did not have a problem with letting people in – it was getting out that was the problem. In HPPS Harry, Ron and Hermione need to enter the rooms located under the hatch to get a hold of the Philosopher’s stone before anyone else does, but since Fluffy is persistently overlooking the hatch this becomes a challenge. The solution is taken from another Greek myth; namely that of Argos, making the scene a hybrid of more than one myth from classical antiquity. Argos was a beast with a hundred eyes who guarded the nymph Io on demand of Hera. Zeus sent Hermes to save Io, and he did so by giving the beast some magical herbs and playing the flute which made Argos fall asleep – thereby enabling Hermes to kill the beast.[24] In HPPS it turns out that the only thing that can render Fluffy harmless is when someone plays him music, as this makes him fall asleep as well. Harry, Ron and Hermione do not kill Fluffy the three-headed dog since killing a dog, three-headed or not, would be too much for a modern-day dog-loving audience. Yet the result remains the same; Io is taken from Argos, and the Philosopher’s stone is taken from Fluffy.

All in all these three examples mirror their ancient predecessors to a degree too identical to be coincidental. This means that HPPS can be labelled a hybrid – a mix of myths and sources merged to form something new. But since anything can happen in a magical universe, the mix of a Greek and British past combined with Rowling’s own imagination works.

The relevance of the work

When the first Harry Potter book came out in 1997, the readers may not have had a completely similar work in their frame of reference for comparison, but films or books involving magic or mystical events experienced an upward curve in the 90’s and the 00’s giving us films and shows like Hocus Pocus (1993), The Craft (1996), The X-Files (1993-2018), Sabrina, the Teenage Witch (1996-2003) and Charmed (1998-2006).[31] The release of the film HPPS in 2001 thereby had the opportunity to ride the wave which started rolling the decade before. But the Harry Potter series did not just become popular thanks to other films and series paving the way. In Fantastik in Literatur und Film Ulf Abraham points out that the combination of the familiar and the fantastic, the known and the unknown makes the narrative believable and facilitates the readers’/viewers’ identification with the plot, events and characters.[32] The same is underlined by Irene Visser and Laura Kaai in “The Books That Lived: J.K. Rowling and The Magic of Storytelling”: “Rowling’s unique achievement in the Potter series, […] is to create an amazing hybrid world of the mundane and the marvellous, of realism and fantasy intertwined, which offers readers the pleasant thrill of the new as well as the equally pleasant recognition of the familiar.”[33] The Harry Potter universe works because it is relatable to all of us. The awkward boy who does not seem to fit in, his joy when he finally does, his experiences of tragic loss, wonderful friendships and love could easily be a metaphor for anyone coming of age or for life itself. Released only two months after the attack on The World Trade Center the film offered the world a positive input and maybe even a believe that miracles can happen when you least expect it.

Impact

Early on Rowling made it clear that the Harry Potter series would be comprised of no more than seven books, but the books’ and films’ success had the audience crying out for more. This meant that Rowling offered us a look at the past as well as the future of the beloved characters. The Fantastic Beasts series now planned to span five films, works as a prequel to the events displayed in Harry Potter, and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child playing out in Harry Potter’s future gave the fans of the series the closure they needed. The new additions mean more books, movie and theatre tickets sold, but the series has also had an impact on tourism. Leaning on Krasilnikoffs thoughts on a spatial aspect, the audience’s desire to visit the places shown and described in the books and films have meant that a whole industry of film tourism had seen the light of day. This means more visitors at obvious places like Warner Bros. Studios displaying whole sets, but also props like clothes, food and drink from the series.[34] It means more visitors at Gloucester Cathedral where some of the scenes taking place at Hogwarts were filmed, and other than that castles and even viaducts like the Glenfinnan Viaduct in Scotland sees an increasing number of visitors. Fiona Hyslop the Scottish Tourism Secretary has stated that: “The growing popularity of our stunning natural scenery and rich historical sites is great for bringing jobs and investment to our communities, but can also put pressure on communities, services, transport and facilities – particularly in rural areas.”[35] Film tourism offers possibilities to the sites in question, but it also poses a threat to the sites suffering under the wear and tear of an increasing number of more or less well behaved visitors – something that is also the case for historic landmarks such as the Colosseum in Rome regularly hit by vandalism in the form of graffiti. This leads to more jobs serving the tourists as well as more jobs cleaning up after them and protecting the sites – indeed a two-sided coin.

Conclusion

As shown above HPPS contains several references to Greek mythology as pointed out and analysed by a means of combining the fields uses of history and reception studies. The likeness of the ancient myths to the scenes presented in HPPS as well as the fact that Rowling studied Classics at Exeter University makes us believe that the use is not coincidental. HPPS can therefore be labelled as a hybrid – though this will not be obvious to everyone watching the film. The film is perfectly watchable without knowledge of Odysseus, Kerberos and Narcissus, but knowing about these myths adds another layer to the film and the interpretation. The scenes and characters are relatable even though they are set in a magical universe, but the themes are universal, which is why the Harry Potter phenomenon has managed to speak to people across time, place and age.

Despite the original story’s span of seven books the life of Harry Potter, his past and future lives on, and given the ongoing popularity of the franchise and fantasy as such I feel fairly safe in predicting that we have not seen the last spinoff of this particular universe yet.

Bibliography

Books and articles

Abraham, Ulf. 2012. Fantastik in Literatur und Film. Ein Einführung für Schule und Hochschule. Erich Schmidt Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin

Hardwick, Lorna. 2003. Reception studies. Cambridge University Press

Hofmann, Dagmar. 2015. “The Phoenix, the Werewolf and the Centaur: The Reception of Mythical Beasts in the Harry Potter Novels and their Film Adaptations” in Ancient Magic and the Supernatural in the Modern Visual and Performing Arts. Edited by Filippo Carlà and Irene Berti, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Homer. 2002. Odysseen. Translated by Otto Steen Due. 2. edition, Gyldendal

Jauss, Hans Robert. 1981. ”Litteraturhistorie som udfordring til litteraturvidenskaben” in Værk og læser en antologi om receptionsforskning. Edited by Michel Olsen and Gunver Kelstrup. Borgens Forlag, Holstebro

Jensen, Bernard Eric. 2003. Historie – livsverden og fag. Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag A/S, København

Karlsson, Klas-Göran. 2003. ”The Holocaust as a Problem of Historical Culture” in K.G. Karlsson og U. Zander (editor) Echoes of the Holocaust. Historical Cultures in Contemporary Europe. Nordic Academic Press

Krasilnikoff, Jens A. 2012. ”Antikken på film: mellem klassisk reception og historiens brug” in Temp vol. 4

Liddell, Henry George, Scott, Robert & Jones, Sir Henry Stuart.(LSJ) 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Ovid. 2005. Ovids Metamorfoser, translated by Otto Steen Due. 2nd edition, Gyldendal

Rowling, J.K. 1997. Harry Potter og De Vises Sten. Translated by Hanna Lützen. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Great Britain

Tortzen, Chr. Gorm. 2009. Antik mytologi. 3rd edition, Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen

Tortzen, Chr. Gorm. 2017. Article about ”Argos” in Den Store Danske, Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi

Visser, Irene and Kaai, Laura. 2015. “The Books That Lived: J.K. Rowling and The Magic of Storytelling” i Brno Studies in English Vol. 41, No. 1

Warring, Anette. 2011. “Erindring og historiebrug – Introduktion til et forskningsfelt” in Temp vol. 2

Zander, Ulf. 2001. Fornstora dagar, moderna tider. Nordic Academic Press, Lund

Film/tv-shows/plays

Alexander. 2004. Warner Bros., Intermedia Films, Pacifica Films, Egmond Film & Television, France 3 Cinéma, IMF Internationale Medien und Film GmbH & Co. 3. Produktions KG, Pathé Renn Productions, WR Universal Group

Charmed. 1998-2006. Spelling Television, Northshore Productions, Paramount Pictures, Viacom Productions

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. 2016. Heyday Films, Warner Bros.

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald. 2018. Heyday Films, Warner Bros.

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. 2016. Written by J.K. Rowling, Jack Thorne and John Tiffany. Premiered at the Palace Theatre

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. 2001. Warner Bros. Heyday Films, 1492 Pictures

Hocus Pocus. 1993. Rhythm and Hues Studios, Touchwood Pacific Partners 1, Walt Disney Pictures, Walt Disney Studios

Sabrina, the Teenage Witch. 1996-2003. Finishing the Hat, Hartbreak Films, Viacom Productions

The Craft. 1996. Columbia Pictures Corporation, Red Wagon Entertainment

The X-Files. 1993-2018. Ten Thirteen Productions, 20th Century Fox Television, X-F Productions

Webpages

Film statistics and facts: www.IMDb.com

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: https://www.harrypottertheplay.com/uk/about/

Irish Examiner: https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/world/viaduct-featured-in-harry-potter-films-to-benefit-from-3m-tourism-fund-873810.html

Photos of Gloucester Cathedral: https://www.gloucestershirelive.co.uk/whats-on/whats-on-news/gallery/harry-potter-scenes-shot-gloucester-53277

Photo of Kerberos: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herakles_Kerberos_Eurystheus_Louvre_E701.jpg?fbclid=IwAR3MOeKhxFRN3rb14he4_5r1yjUAnzK5GvE9JpZXQ7oL4S8b-3T3NAWw5_8

J.K. Rowling: https://www.jkrowling.com/about/

Warner Bros. Studios: https://www.wbstudiotour.co.uk/

Other

Jensby, Louise. 2018. “Antikken på film: Odysseen set gennem et kalejdoskop. Et speciale om brugen af det antikke værk Odysseen i Hollywoodproduktioner.” Translated by Louise Jensby. Speciale i historie og oldtidskundskab ved Aarhus Universitet, Unpublished

References

[1] Liddell, Scott & Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon, “μῦθος” (mythos), A II 2., II 3., II 4. FX. “professed work of fiction, children’s story, fable”

[2] https://www.jkrowling.com/about/

[3] This section is based on and translated from my Master’s Thesis “Antikken på film: Odysseen set gennem et kalejdoskop. Et speciale om brugen af det antikke værk Odysseen i Hollywoodproduktioner.”, 16-20

[4] Bernard Eric Jensen, Historie – livsverden og fag, 67. My translation

[5] Ibid., 68

[6] Klas-Göran Karlsson, ”The Holocaust as a Problem of Historical Culture” in K.G. Karlsson and U. Zander (red.) Echoes of the Holocaust. Historical Cultures in Contemporary Europe, 39-42. Also see Anette Warring “Erindring og historiebrug – Introduktion til et forskningsfelt” in Temp vol. 2 2011, 24-25, and Ulf Zander Fornstora dagar, moderna tider, 52-57 for an examination of Karlsson’s typologies

[7] Yet it is possible to apply more than one category to a certain case, giving us the opportunity to widen our view of the case in question

[8] Jens A. Krasilnikoff, “Antikken på film: mellem klassisk reception og historiens brug”, 173

[9] Ibid., 173-174

[10] Only Krasilnikoff briefly addresses Oliver Stone probably looking into sources from Classical Athens for the film Alexander, 175

[11] Hans Robert Jauss, ”Litteraturhistorie som udfordring til litteraturvidenskaben”, 59. My translation

[12] Ibid., 62-65

[13] Lorna Hardwick, Reception Studies, 5

[14] Ibid., 9-10

[15] https://www.jkrowling.com/about/

[16] Dagmar Hofmann, “The Phoenix, the Werewolf and the Centaur: The Reception of Mythical Beasts in the Harry Potter Novels and their Film Adaptations”, 163

[17] https://www.jkrowling.com/about/

[18] HPPS, 11.47-17.40

[19] Od. 10, 135-209

[20] Ibid., 237-243. Circe is also mentioned as a famous witch in the first Harry Potter book. Harry Potter og De Vises Sten, 104

[21] HPPS, 16.54

[22] Early on in the book behind the film, Dudley is described as looking like a ”pig in a wig”, meaning that Hagrid’s magic trick only enhances Dudley’s resemblance with this particular animal. Harry Potter og De Vises Sten, 23

[23] HPPS, 59.55-1.00.21 and 1.49.57-1.51.35

[24] Chr. Gorm Tortzen, Antik mytologi, 274, see also Chr Gorm Tortzen, ”Argos” in Den Store Danske

[25] Pictures Kerberos taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herakles_Kerberos_Eurystheus_Louvre_E701.jpg?fbclid=IwAR3MOeKhxFRN3rb14he4_5r1yjUAnzK5GvE9JpZXQ7oL4S8b-3T3NAWw5_8, picture of Fluffy screenshot by Louise Jensby

[26] HPPS, 1.28.00-1.29.51

[27] HPPS, 1.30.15-1.30.45

[28] HPPS, 1.30.50-1.32.20

[29] Ovid, Metamorfoserne 3, 341-510

[30] Picture of Narcissus taken by Louise Jensby in Pompeii, picture of Harry Potter screenshot by Louise Jensby

[31] See www.IMDb.com for more statistics and facts about these films and series

[32] Ulf Abraham, Fantastik in Literatur und Film, 23

[33] Irene Visser and Laura Kaai, “The Books That Lived: J.K. Rowling and The Magic of Storytelling”, 201

[34] https://www.wbstudiotour.co.uk/

[35] https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/world/viaduct-featured-in-harry-potter-films-to-benefit-from-3m-tourism-fund-873810.html

[36] For pictures from Gloucester Cathedral as shown in the Harry Potter movies see: https://www.gloucestershirelive.co.uk/whats-on/whats-on-news/gallery/harry-potter-scenes-shot-gloucester-53277

Schreibe einen Kommentar