Classical Trek – 4000 years of boldly going (Gastbeitrag von Daniel B. Unruh)

[The English text begins after a short introduction in German]

Daniel B. Unruh ist ein britischer Althistoriker, der sich hauptsächlich mit der Entwicklung des politischen und sozialen Denkens in der antiken griechischen Welt befasst. In diesem Rahmen beschäftigt er sich u.a. mit monarchischen Herrschaftsformen wie dem Königtum und der Tyrannis sowie der Frage nach der Interaktion der Bürger griechischer Stadtstaaten mit auswärtigen Alleinherrschern. Zu seinen weiteren Forschungsfeldern zählen Epos, Tragödie und Komödie im antiken Griechenland, die Konstruktion der Rolle des Kaisers in der julisch-claudischen Dynastie sowie das Verhältnis zwischen öffentlichem Raum und politischer Macht im griechischen und römischen Denken. Derzeitig lehrt Daniel in Cambridge Altgriechisch sowie griechische Literatur und Geschichte. Umso spannender ist es, dass er mit Historiai einen Blog ins Leben gerufen hat, der diesem Blog inhaltlich sehr ähnlich ist und der der geneigten Leserschaft wärmstens empfohlen sei. Im Folgenden Beitrag, der ursprünglich hier erschien, macht sich Daniel äußerst spannende Gedanken zum berühmten „To boldly go where no-one has gone before“:

„From meeting the god Apollo in The Original Series, to the Roman-inflected Terran Empire in Star Trek: Discovery, Star Trek has always drawn heavily on ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration. Since both Star Trek and Classics have been important parts of my life from a young age, I’ve decided to take a look at some of the more interesting way the franchise has engaged with the ancient world, whether through direct allusion or more subtle thematic patterning.

In this first instalment, I begin by looking at the very ancient roots of one of pop culture’s most famous split infinitives.

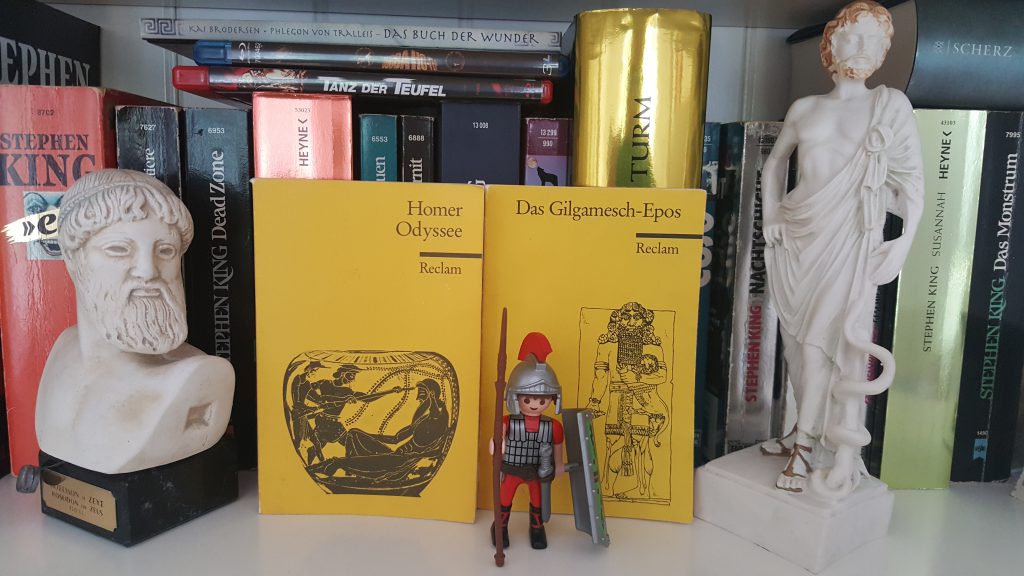

Photo: Michael Kleu

To explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no-one has gone before.

This is, of course, the conclusion of the phrase that opens the credit-sequences of both the original Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation. (1) This phrase not only describes the mission of the Starship(s) Enterprise, but also sets out the outlook of Star Trek as a whole: courageous exploration of the unknown, and the peaceful and scientific search for different species and cultures.

As my friend Philip once pointed out to me, the direct inspiration for this phrase would seem, oddly enough, to stem from a work by H. P Lovecraft, a writer whose grim view of the universe and wide array of prejudices stand in sharp contrast to the more optimistic and inclusive vision of Star Trek. In his surreal novella The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, Lovecraft describes his hero, after entering into a fantastic dreamworld, resolving “to go with bold entreaty whither no man had gone before.”

The sentiment on which both Lovecraft’s passage and the Star Trek catchphrase are based, however, goes back much much further. The celebration of exploring the unknown and encountering new cultures and peoples is articulated in one of the earliest works of European literature. The Odyssey, composed some time between 750 and 650 BCE, opens with a powerful evocation of its hero Odysseus as traveller, captain, and explorer:

Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ

πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν·

πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω,

πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν,

ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων.

Sing to me Muse of a man, a man of myriad ways,

who was driven far afield since he sacked Troy’s sacred city.

He saw the cities of many peoples and came to know their minds,

he suffered many pains in his heart upon the sea

as he strove to save his life and bring his comrades home.

As these opening lines suggest, Odysseus can be seen as the prototype of most of the Star Trek captains. They describe someone who travels far across their culture’s “final frontier” – outer space for us, the uncharted seas for the ancients; who braves terrible dangers, always anxious for the safety of the souls under their command; who revels in discovering and learning about previously unknown creatures and societies. The strange lands Odysseus encounters sound much like worlds that the various Star Trek crews might (and in some cases, do) encounter. A place where people live in static bliss, under the power of a potent drug; a land of uncivilized giants, against whose brute strength only a cunning mind can prevail; a world ruled by a powerful being who can bend reality – and our intrepid captain – to her will.

In its depiction of going beyond the known world and discovering new forms of life and ways of living, and its celebration of thought and language over force and violence, the Odyssey anticipates many of the themes that have made Star Trek so beloved. Its intelligent, eloquent, and dedicated hero Odysseus is in many ways the spiritual ancestor of Kirk, Janeway, Picard, and their fellow Starfleet captains.

This might seem a nice place to wrap up, but the story actually doesn’t stop here. The image of someone who boldly goes where none has gone before is in fact older still. While the Iliad and Odyssey are the oldest texts in Europe, they are far from the world’s oldest. It has long been recognised that these Homeric epics owe much to earlier Near-Eastern epic traditions. One of the pre-eminent epics of the ancient Near East was The Epic of Gilgamesh. This text, describing the adventures of the Sumerian king of Uruk, has been considered the world’s earliest extant piece of long-form literature. Based on material composed in Sumerian around 2100 BCE, this epic was copied, reworked, and translated for around 2000 years. In addition to the original Sumerian fragments, we have versions written in Akkadian, Elamite, Hittite, and Hurrian. The opening of the Akkadian version, generally regarded as the standard text of the epic, once again celebrates a man who boldly goes:

He [learnt] the totality of wisdom about everything.

He saw the secret and uncovered the hidden,

he brought back a message from the antediluvian age.

He came a distant road and was weary but granted rest,

he set down on a stele all his labours.

(lines 7-10, translated by A. R. George).

Here too we have a celebration of the hero as explorer, travelling great distances to uncover new knowledge. Gilgamesh has less in common with the heroes of Star Trek than Odysseus: he is a man who generally prefers brawn over brain, and rather than shepherding a crew through the unknown, in his adventures he is either solitary, or accompanied only by his beloved companion, the wild-man Enkidu. (2) Nevertheless, in its celebration of a hero who crosses space to bring back knowledge, the epic stands as the first celebration of the impulse celebrated in the Odyssey, in countless works of literature since, and in the various incarnations of Star Trek: the impulse to boldly go where no-one has gone before.

Photo: Michael Kleu

A final note:

In the preface to this post, I talked about “to boldly go where no-one has gone before” as “one of pop culture’s most famous split infinitives.” The fact that “to boldly go” is a split infinitive – that is, the adverb is between the “to” and the verb – has caused a certain amount of irritation, as there’s a widespread belief that this kind of construction is somehow wrong. Split infinitives are, however, a perfectly natural English form – they make perfect sense, and often (as here) sound better rhythmically than alternative forms. The only reason that split infinitives are criticised is due to attempts to make English grammar more like that of Latin and Ancient Greek. In those languages, the infinitive forms are a single word. English writers and teachers of past ages, having learned their grammar largely from Latin and Greek lessons, took to thinking about English infinitives also as single units, and therefore started feeling it was inappropriate to put anything inside them. But English is not Latin or Greek, English infinitives are two words, and really there’s no reason not to boldly split infinitives if you so desire.

If you are interested in reading more about classical reception in Star Trek: click here.

Footnotes:

(1) The original Star Trek, of course, said “where no man has gone before,” but The Next Generation and most of the films updated it to a more inclusive form.

(2) Though one could see the deep connection between Gilgamesh and the not-entirely-human Enkidu as echoed in the relationship between Captain Kirk and the half-human, half-Vulcan Spock in Star Trek.“

Der zitierte Beitrag wurde ursprünglisch hier veröffentlicht, wo sich noch viele weitere spannende Artikel zur Antikenrezeption in Science Fiction, Horror und Fantasy finden lassen.

- Doctor Who trifft Sokrates und Platon im antiken Athen: The Chains of Olympus (Comic, 2011–2012) - 31. August 2024

- Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher Geschichte(n) in Peter S. Beagles „Das Letzte Einhorn“ - 16. Juli 2023

- Römische Arenen und Wilder Westen: Jasmin Jülichers „Stadt der Asche“ - 4. Oktober 2022

0 Kommentare