„Animal Farm“ and „Farenheit 451“ – Classical Reception in Dystopias (by David Hogg)

Since David Hogg’s great page „Ars Longa. An Index of Every Classical Reference Ever!“ will go offline soon, David agreed to move its content to fantastischeantike.de. On this page you’ll not only see some of his lovely drawings, but also his thoughts on „Animal Farm“ and „Farenheit 451“:

„Animal Farm“ by George Orwell

George Orwell’s „Animal Farm“ and Emporor Augustus

George Orwell’s exploration of politics and the corrupting influence of power has outlasted the system it set out to satirise and is now firmly in the hands of the modern reader. The text is flexible enough to be superimposed on new dystopias and continues to find relevance today. In a similar way to Animal Farm, Classics has remained current and it is therefore no surprise to find Classical echoes in Orwell’s masterpiece. The oppressive porcine leader of the farm is called Napoleon, which is a name synonymous with empire and imperial ambition. Saddled with this name, he is only one historical step away from Emperor Augustus and when the 7th law on Animal Farm is changed from „All animals are equal“ to „All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others“, we clearly see the ideas of the princeps senatus adopted by a new pig-Emperor. Augustus took the title of princeps senatus to convince the citizens of Rome that the Republic was still alive and that although he had power, he did not have more power than the senate; he definitely was not a king! This of course was not true and it is a great example of what Orwell labelled doublespeak. Augustus may have been one of the ‚first among many‘ to successfully employ such linguistic slight-of-hand, but he has not been the last.

Talking animals in „Animal Farm“ and Aristophanes‘ „The Birds“

Talking animals are with us from the day we are born. A baby’s first book will often have an animal talking the infant through a narrative and the voices of animals are sounds that never leave us. Loquacious animals appear in cartoons, books and movies and they include some of our favourite characters: Mickey Mouse, Aslan, Rocket, Kermit and Howard the Duck, to name just a few. In texts, animals are allowed to behave in ways and say the things that people cannot – they can be naive without being stupid, they can be honest without needing to be wise and they can be political without being… political.

George Orwell knew this and so did Aristophanes. Both writers have used talking animals to say what was perhaps unspeakable in their own societies – either because of censorship or because if humans said what the animal characters said, an audience may feel as though they are listening to a sermon rather than a story, which could turn people away from the desired message; and it is those who need politics the most who are the ones least likely to seek it out and most likely to turn away from tub thumping political stories.

Orwell recognised this and gave Animal Farm the subtitle A Fairy Story. He used his idealistic animals as an allegory to deal with the heavyweight topics of communism, capitalism, tyranny and totalitarianism. By setting his story on a farm he was able to take away the weight of history and the complications of political theory which would have been present in a ‘human story’. His decision to anthropomorphise the animals allowed him to simply and effectively get to the crux of his argument.

In Birds, Aristophanes employed the same methods nearly 2500 years before Orwell. Both Animal Farm and Birds deal with the search for a utopia where ‘a kind of man’ can turn its back on the suffocation of modern life and get back to basics, start again, and focus on what is important. Both texts see an animal world as a place that has the greatest potential for optimism in the minds of the protagonists. Both communes are also founded by a sage-like visionary (Old Major and Peisetairos) who reveals ‘the truth’ about the subservient lives of the animals – a life that in the ‘new worlds’ they will not have to suffer. But neither Cloudcuckooland nor Animal Farm can escape the shadow of man which falls over both Utopias. Both host unwanted visitors determined to mire the new free zones in the shackles of the ‚old world‘ and both have leaders who succumb to the temptations and corruptions of the ‚old world‘, such as money, power and sex.

There are lots of differences between the messages of both texts, but it is in the brutal critiques of accepted systems where these writers find the clearest harmony. “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others”, written by Squealer (in Animal Farm) topples communism as equally as the the vote between Poseidon, Herakles and Triballus (which Poseidon loses – to a gluttonous bore and an idiot) highlights the shortcomings of democracy (in the opinion of Aristophanes). It certainly helps that animals deliver these blows to the systems – we seem to listen more carefully when an animal speaks.

„Fahrenheit 451“ by Ray Bradbury

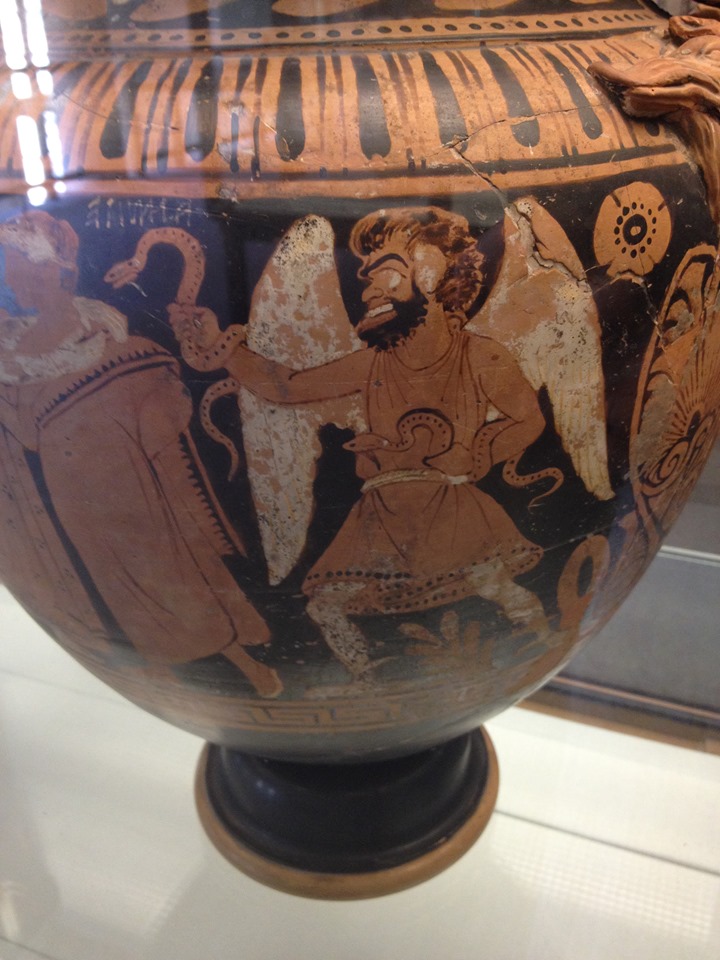

Hercules in „Farenheit 451“

“Do you know the legend of Hercules and Antaeus, the giant wrestler, whose strength was incredible so long as he stood firmly on the earth. But when he was held, rootless, in mid-air, by Hercules, he perished easily. If there isn’t something in that legend for us today, in this city, in our time, then I am completely insane.”

Fahrenheit 451 is a dystopian novel that deals with the idea that books are irrelevant and/or subversive and everyone is only interested in flashing entertainment screens, immediate fulfilment and the championing of ignorance. Apparently this book is set in the future, but like all good Sci-Fi (particularly those written some time ago), it resonates with us today. The quote above is said by ‘book lover’ Faber to ‘book destroyer’, the Fireman Montag. Faber is trying to explain what good literature is and how it makes a difference to the world we live in to the increasingly self-aware Montag.

It is a highly ambiguous quote. Initially it seems that Hercules represents the pursuit of knowledge and that in order to gain this, a person in Montag’s world needs to remove the barriers that stand in their way, preventing them from feeling ‘the earth’. This can be taken very literally; we need to disconnect from technology which draws our focus away from the world around us. Faber seems to be saying that a person needs superhuman strength and savvy, like Hercules, to overcome the all-controlling state; as Hercules demonstrates, there is always a way, if there is the will.

However, the perceived ‘good vs bad’ motif could be turned on its head. Is Antaeus the knowledge hunter who has been disconnected from the earth by the Herculean state? Is Faber saying that we are no longer connected to the earth and the people around us and therefore we are losing our strength as a species? When we think today about our rampant consumerism and our disregard and ignorance for the processes that deliver our desires, I think it seems clear that Faber is saying that we need to establish our roots again, perhaps literally; we need to understand where food comes from, learn about history and explore the genius of mankind. We are a weaker species if we do not understand the world around us.

There is also a ‘Homeric’ feel to the end of the book as we discover that there is a group of people who have learnt a work of literature off-by-heart so that when they are needed, they can recite the work of art back to humanity and thus our canon will live again. The Homer we have today may not be exactly as it was originally performed, but it is a gift nonetheless from the people who tried to memorise it in Ancient Greece and they have therefore allowed us to keep connected to our past.

„Fahrenheit 451“ and Icarus

In Bradbury’s dystopian vision of the future, reading is banned and any literature that is discovered has to be burnt and any readers can be executed. However, Montag is not like the other Firemen; he has a natural inquisitiveness and although he doesn’t understand what books are, he knows that they are important. Montag then sets out to find someone who can teach him what books mean, why they are special and how to understand them. He successfully finds a guide, but his daring is rewarded with exposure to the authorities and he becomes the subject of a manhunt carried out by his old Firemen crew.

Once Montag has been discovered, Beatty, his station commander states, “‘Old Montag wanted to fly near the sun, and now that he’s burnt his damn wings he wonders why.’” This is clearly an allusion to Icarus, who against the better advice of his father, flew too close to the sun. The Greek myth of Icarus has often been interpreted as a warning to young people about ignoring parental advice; additionally it can also be seen as a tale of man’s arrogance and nature’s ‘slap down’. Other, more positive readings can also be made. For example, it can be seen as a story about ‘burning brightly’ and the preference to live in excitement at the edges rather than exist in mediocrity at the centre. Additionally it can be seen as a tale of human inquisitiveness – what is it like to push the limits; what happens if I do this…?

All of these interpretations can be applied to Montag. He broke the rules and was punished. He thought he knew better than his superiors. He wanted to see what was ‘behind the curtain’. And finally he preferred to allow his inquisitiveness to be fired up, rather than left to smoulder away.

It turns out that Montag is right to test the rules and his journey of discovery saves him. Icarus too can say that he was right – he did something that nobody else has done; it may not have saved him, but it did immortalise him.

As for Beatty, his quote betrays his own knowledge of literature and exposes the idea that those in power seek to control the access to information of the people below them. Perhaps Beatty and his kind are trying to do the impossible and they are in fact Icarus, fighting a ‘sun’ that will always revolt and win in the end.

- Doctor Who trifft Sokrates und Platon im antiken Athen: The Chains of Olympus (Comic, 2011–2012) - 31. August 2024

- Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher Geschichte(n) in Peter S. Beagles „Das Letzte Einhorn“ - 16. Juli 2023

- Römische Arenen und Wilder Westen: Jasmin Jülichers „Stadt der Asche“ - 4. Oktober 2022