Veröffentlicht: 23. Januar 2019 – Letzte Aktualisierung: 21. September 2022

The socioreligious ritual of hospitality has long been regarded as an important component in our proper understanding of the Homeric Odyssey. One might turn, in this regard, to Steve Reece’s important monograph The Stranger’s Welcome (1993), which lists the typical elements of the Homeric reception scene (he lists over thirty-five repeatable [sub]elements). Scholars such as Reece and Glenn Most have illustrated how the epic poem presents different models of hospitality: from Telemachus’ benevolent reception at Nestor’s home to Odysseus’ somewhat ambiguous reception among the Phaeacians (an unresolved issue in the scholarship) to the outright blasphemy of Polyphemus (his macabre ‘guest-gift’ to Odysseus is to eat the hero last). While the plot of the Odyssey has been regarded as a nostos, a story of homecoming, it might be more reflective of the epic poem in its entirety (not just Book 5 to 13) to think of it in terms of a quest for attaining hospitality—a nostos, then, not merely in a mere physical sense of returning home but also in the sense of recovering what a home, or oikos, means or should represent.

The first four books of the Odyssey follow the story of Telemachus. His home is being overrun by his reckless guests, the suitors, who are fast consuming his livestock (thus, depleting his ‘property’) and who are trying to win the hand of his mother Penelope in the absence of his father. Telemachus travels abroad to Nestor in Pylos and Menelaus in Sparta to gain news of his father, and during these journeys he is richly entertained by hospitable, generous hosts. The most famous part of the Odyssey, Book 5 to 12, describe Odysseus’ stay in Scheria among the Phaeacians, where he asks for their help in arriving home, and his famous narrative the Apologoi, during which he tells of the many troubles he and his men endured on inhospitable shores. Finally, the last half of the epic poem deals with the restoration of the host’s property and the punishment of abusive guests, through Odysseus’ slaughter of the suitors. The Odyssey therefore provides a narrative progression, from an initially unsatisfactory state of hospitality to a series of episodes in which different forms of reception (positive (Nestor), negative (Polyphemus), or somewhat ambiguous (Circe)) are represented to the heroes and, finally, to a resolution where the earlier crimes against the home are atoned for.

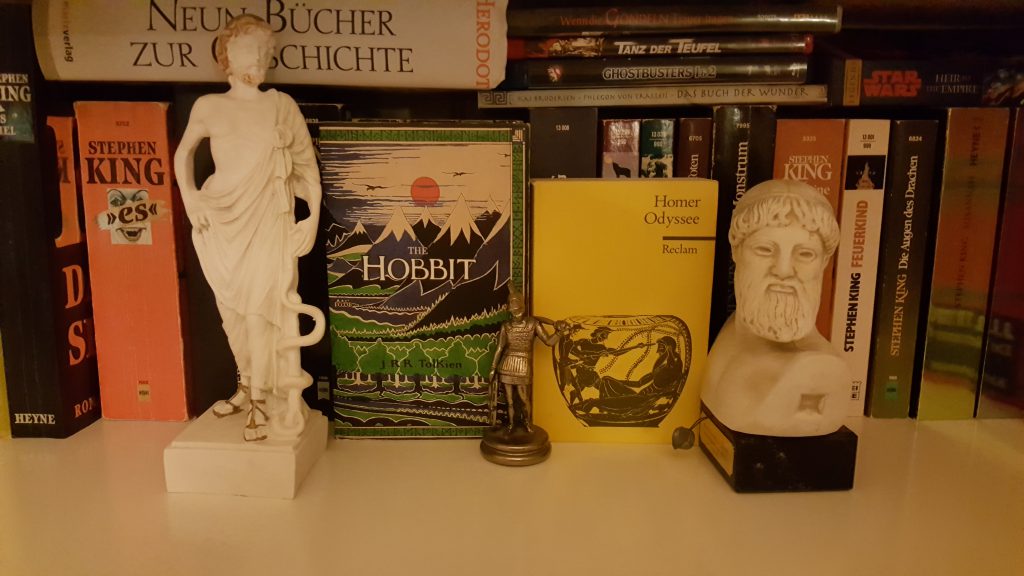

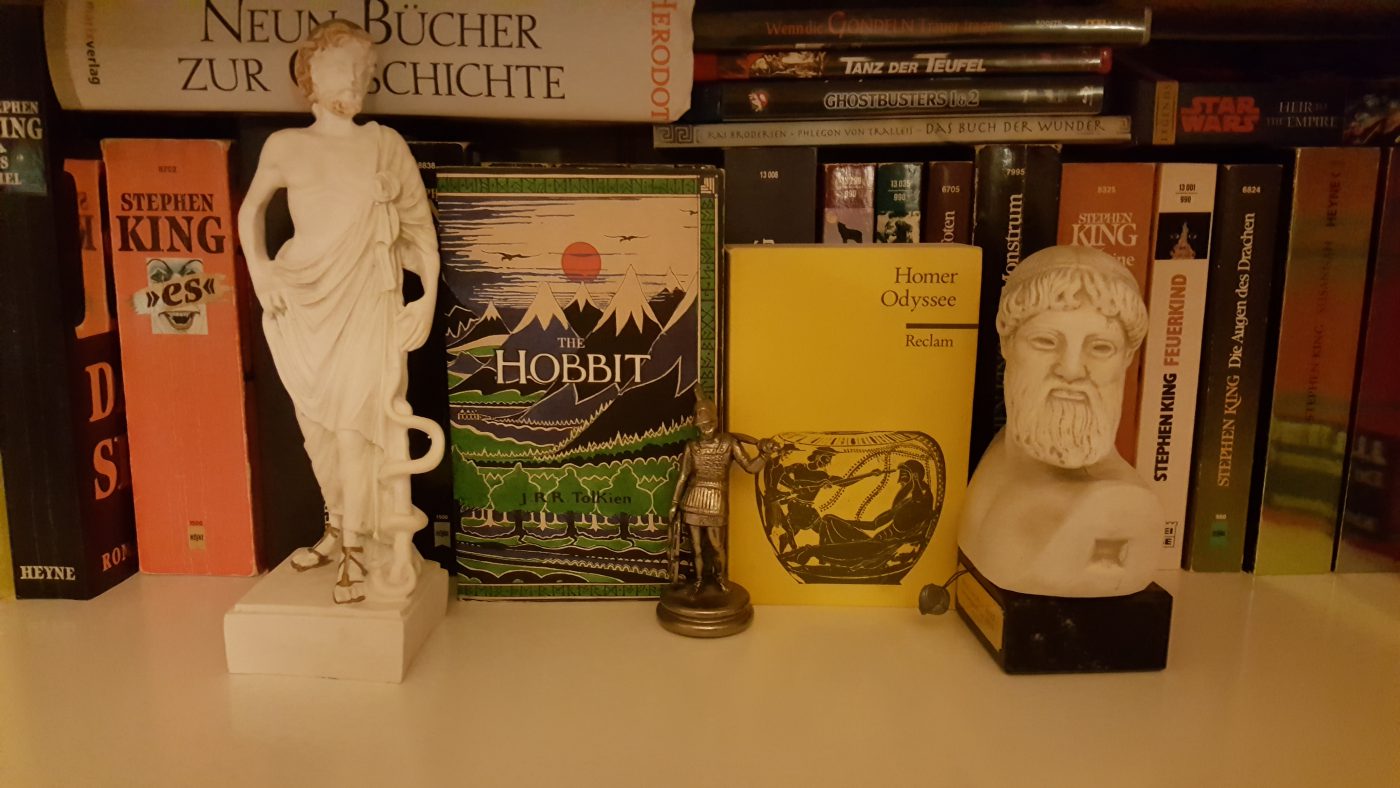

Photo: Michael Kleu

This narrative progression in hospitality in the Homeric poems provides a blueprint for appreciating one of the most popular and liked children’s stories of the twentieth century—J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937). The quest of The Hobbit can also be divided into three parts. (i) The first part reveals the inadequacies of Bilbo as a host and the dwarves as guests; (ii) the second part involves the company of travellers enduring various kinds of reception by hosts—malevolent, benevolent, or something in-between; and (iii) the final part resolves the earlier inhospitalities.

(i) At the beginning of the story, the hobbit Bilbo Baggins is an ambivalent host, content to open his doors only to those individuals who will not threaten to disrupt or remove him from the comfort of his paradisiacal home, Bag End. The wizard Gandalf soon realises the conditionality of Bilbo’s reception when he arrives at the hobbit’s doorstep (it will, indeed, remain a ‘good morning’ for Bilbo, whether the wizard-guest likes it or not). Most importantly, guests who require help with anything, for example, adventures, are not welcome to the hobbit since they will then disrupt the stagnant comforts of the home. The Odyssey itself provides some examples of hosts who are surrounded by otherworldly comforts such as Calypso in Ogygia and the Phaeacians in Scheria, both of whom offer to share the pleasures of their homes with Odysseus but are slightly more reticent to help him in expediting his homecoming. Odysseus, of course, stays in Ogygia for seven years, and he has to plead his case to the Phaeacians, whose easy life means they cannot readily understand his sufferings.

While Bilbo’s conception of hospitality is somewhat limited and conditional at the start of The Hobbit, so too is that of the thirteen dwarves who abruptly arrive at his home. The dwarves threaten to eat Bilbo out of house and home and to break all his cutlery (this is put into verse). Although the dwarves are not as openly disrespectful to their young, inexperienced host as the suitors are to Telemachus in the Odyssey, the dwarves still have no qualms about risking the life of their host, Bilbo, on their adventures in order to render themselves in possession of a home once more. In short, they have a solipsistic conception of home.

(ii) The central section of The Hobbit is concerned with presenting different models of guest-host situations, many of which can be traced to the Odyssey. For example, the anthropophagous welcome of Polyphemus in the Odyssey is picked up by Tolkien’s three trolls who try to cook up the dwarves. This episode, although also rooted in Nordic fairy tales from the nineteenth century, displays many points of similarity with the Homeric Cyclopeia in spatial or material details—entailing a forest clearing, a cave-home, and references to sheep/mutton—and in the action sequences—most notably, Thorin Oakenshield, the chief dwarf, picks up a branch lit with fire at one end and tries to blind one of the trolls. Finally, in both stories, these dumb brutes are defeated by the verbal dexterity of Odysseus and Gandalf.

There are parallels throughout The Hobbit to other episodes from the Wanderings of Odysseus. After the encounters with the giant, man-eating monsters (cyclopes and trolls), the Ithacans and the dwarven company are offered a brief respite through the benevolent, near perfect receptions of Aeolus and Elrond, respectively; both hosts are divine beings, offer plentiful food to their guests, provide directions or guidance for the path ahead, and are, in differing respects, controllers or pacifiers of nature. In a later episode, the dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf are given a hearty reception by the ‘arctanthrope’ Beorn (a shape-shifter or werebear), who lends them his ponies to take them to the borders of his land—but no further. The dwarves, however, later contemplate stealing these ponies and taking them further on their path into Mirkwood so as to expedite their voyage; it is only the sound advice of Gandalf, though, which warns them of the wrath of Beorn. This narrative provides a contrast to that of the Island of Helios in Odyssey 12, wherein Odysseus’ men ignore the hero’s advice and slaughter the cattle of the Sun, for which they are destroyed by the wrath of Zeus.

(iii) Towards the end of The Hobbit, the dwarves and their leader Thorin have certainly regained their home in a physical sense, but they are far from understanding the reciprocity which lies behind such ownership in the social order of a broader community. The death of the dragon Smaug at the hands of the hero Bard of Lake-town has ensured that the dwarves can once again enjoy the ownership of their home, the Lonely Mountain, but this is at the expense of the home of the people of Lake-town, which is destroyed by dragon fire. However, when these destitute people require aid from the dwarves through the sharing of some of their newly claimed wealth, Thorin shuts up the entrance of his home—this is in spite of the fact that the people of Lake-town entertained and showed hospitality to the dwarves earlier in their expedition (through food, shelter, and gifts).

In a sense then, in The Hobbit, just as in the Odyssey, the correct state of hospitality has to be brought about through a battle in which there is a loss of life of irreverent hosts, and after which there is peace between neighbours, both in Middle Earth and on Ithaca. After the Battle of the Five Armies in The Hobbit, the dwarves come to realise the errors of their ways and disperse a share of their treasure to Bard and thus the people of Lake-town (who now dwell in the restored city of Dale). The lesson in reciprocity is, at any rate, well learnt by Bilbo, in particular, whose home, at the end of the story, is open to “all such folk as ever passed that way” (The Hobbit, Ch. 19). While he is not quite so respected anymore by his insular, somewhat xenophobic neighbours, the hobbit does not care.

Hamish Williams

Author Bio:

Hamish Williams holds a PhD in Ancient Greek Literature from the University of Cape Town (2017). He currently teaches International Studies at Leiden University. From 2019, he will be pursuing a Humboldt Fellowship at the Department of English and American Studies at Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena.

- Stephen Kings SHINING. Analysen, Hintergründe zu den Filmen & Romanen. Buchrezension von Stefan Preis - 21. September 2023

- A Nightmare on Elm Street – Freddy Krueger als antiker Vampir (Stefan Preis) - 1. September 2023

- Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher Geschichte(n) in Peter S. Beagles „Das Letzte Einhorn“ - 16. Juli 2023

Schreibe einen Kommentar